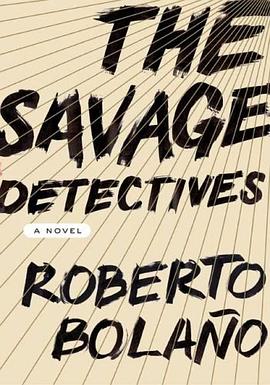

The Savage Detectives pdf epub mobi txt 电子书 下载 2025

- 小说

- 拉美

- Bolaño

- 罗贝托·波拉尼奥

- 拉美文学

- 英语

- 文学

- RobertoBolaño

- 加西亚·马尔克斯

- 拉美文学

- 小说

- 现代主义

- 冒险故事

- 孤独主题

- 智利

- 秘鲁

- 流浪者

- 叙事风格

具体描述

New Year’s Eve, 1975: Arturo Belano and Ulises Lima, founders of the visceral realist movement in poetry, leave Mexico City in a borrowed white Impala. Their quest: to track down the obscure, vanished poet Cesárea Tinajero. A violent showdown in the Sonora desert turns search to flight; twenty years later Belano and Lima are still on the run.

The explosive first long work by “the most exciting writer to come from south of the Rio Grande in a long time” (Ilan Stavans, Los Angeles Times), The Savage Detectives follows Belano and Lima through the eyes of the people whose paths they cross in Central America, Europe, Israel, and West Africa. This chorus includes the muses of visceral realism, the beautiful Font sisters; their father, an architect interned in a Mexico City asylum; a sensitive young follower of Octavio Paz; a foul-mouthed American graduate student; a French girl with a taste for the Marquis de Sade; the great-granddaughter of Leon Trotsky; a Chilean stowaway with a mystical gift for numbers; the anorexic heiress to a Mexican underwear empire; an Argentinian photojournalist in Angola; and assorted hangers-on, detractors, critics, lovers, employers, vagabonds, real-life literary figures, and random acquaintances.

A polymathic descendant of Borges and Pynchon, Roberto Bolaño traces the hidden connection between literature and violence in a world where national boundaries are fluid and death lurks in the shadow of the avant-garde. The Savage Detectives is a dazzling original, the first great Latin American novel of the twenty-first century.

作者简介

For most of his early adulthood, Bolaño was a vagabond, living at one time or another in Chile, Mexico, El Salvador, France and Spain.

Bolaño moved to Europe in 1977, and finally made his way to Spain, where he married and settled on the Mediterranean coast near Barcelona, working as a dishwasher, a campground custodian, bellhop and garbage collector — working during the day and writing at night.

He continued with poetry, before shifting to fiction in his early forties. In an interview Bolaño stated that he made this decision because he felt responsible for the future financial well-being of his family, which he knew he could never secure from the earnings of a poet. This was confirmed by Jorge Herralde, who explained that Bolaño "abandoned his parsimonious beatnik existence" because the birth of his son in 1990 made him "decide that he was responsible for his family's future and that it would be easier to earn a living by writing fiction." However, he continued to think of himself primarily as a poet, and a collection of his verse, spanning 20 years, was published in 2000 under the title The Romantic Dogs.

Regarding his native country Chile, which he visited just once after going into voluntary exile, Bolaño had conflicted feelings. He was notorious in Chile for his fierce attacks on Isabel Allende and other members of the literary establishment.

In 2003, after a long period of declining health, Bolaño died. It has been suggested that he was at one time a heroin addict and that the cause of his death was a liver illness resulting from Hepatitis C, with which he was infected as a result of sharing needles during his "mainlining" days. However, the accuracy of this has been called into question. It is true that he suffered from liver failure and was close to the top of a transplant list at the time of his death.

Bolaño was survived by his Spanish wife and their two children, whom he once called "my only motherland."

Although deep down he always felt like a poet, his reputation ultimately rests on his novels, novellas and short story collections. Although Bolaño espoused the lifestyle of a bohemian poet and literary enfant terrible for all his adult life, he only began to produce substantial works of fiction in the 1990s. He almost immediately became a highly regarded figure in Spanish and Latin American letters.

In rapid succession, he published a series of critically acclaimed works, the most important of which are the novel Los detectives salvajes (The Savage Detectives), the novella Nocturno de Chile (By Night In Chile), and, posthumously, the novel 2666. His two collections of short stories Llamadas telefónicas and Putas asesinas were awarded literary prizes.

In 2009 a number of unpublished novels were discovered among the author's papers.

目录信息

读后感

Bolaño的流水账,我看了一个月。 到了最后,明白了infrarealism, 明白了他为什么要反对Márquez和Paz,和魔幻现实主义的仿效者。 他的长篇小说比短篇好,甚至好过他自己看重的诗歌。把日常生活写出浓郁的暴力。这股浓郁,再也不用贩卖独裁/殖民/战争/政变这些“拉美题材”来...

评分《荒野侦探》的结构像香肠,加西亚•马德罗的故事束住了这本书的两端,让这本本来完全可能无头无尾、无休无止的庞杂之书有了开端和结尾。利马和贝拉诺的经历如肠衣,包裹住丰富的馅料。没有肠衣、线头,就做不成美味的香肠,不过香肠的滋味主要还是在馅料里。在酣畅淋漓、充...

评分 评分很难想象上世纪末还会冒出这么一部了不起的意识流作品,撇开前后的日记部分,《荒野侦探》还真有点《尤利西斯》的派头,而且用纯粹的口语写出了一种令人咂舌的诗意。难怪很多人把该书作者波拉尼奥抬到马尔克斯和略撒的高度了。史蒂文斯说“诗歌是高贵性的公墓”,也就...

评分时间过得真快,很多年前总是觉得2000年太远,所有人为千禧年做着的各种筹备。。。但是现在往回看呢,它又变得更远了。。。前些日子麦田的作者挂了,一些朋友重读小说,发现这个经典已经叫人读不下去了,这个是叫人很为难的东西。但是没有办法,因为大家都开始为年轻时候鄙视的...

用户评价

我爱这本书它一部分是我幻想中的年少回忆一部分是实践一部分是未来梦境的地图引用kierkegaard the experience of despair n guilt creates in us an awareness of qualitative differences in types of existence..some types r more authentic than others Arrivg at au exp is not an intellectual matter bt a mtr of faith and commitment a continuous process of choice in the presence of varieties either-or

评分流水账天才。

评分艾玛花了三个月才把这本砖头书啃完。。。日记体+访谈录+日记体,勾勒出一帮嬉皮诗人的传奇生活片段。一大把碎片,其中有些碎片故事蛮有意思的,发现能够跟前面的碎片串在一起也有着极强的游戏感。波拉尼奥喜欢拽人名,拽术语。。。略抓狂。

评分Time flows like water under the bridge. Or is it bridge under the water?Settled be the memories of dust, on the velvety skin of youth, on the lukewarm domesticity of adulthood, on the thin sheets of old age.

评分how i wish it would never have an ending

相关图书

本站所有内容均为互联网搜索引擎提供的公开搜索信息,本站不存储任何数据与内容,任何内容与数据均与本站无关,如有需要请联系相关搜索引擎包括但不限于百度,google,bing,sogou 等

© 2025 book.quotespace.org All Rights Reserved. 小美书屋 版权所有