具體描述

媒體推薦

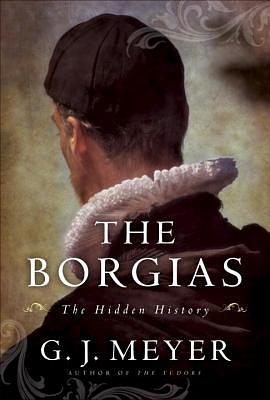

“A vivid and at times startling reappraisal of one of the most notorious dynasties in history . . . If you thought you knew the Borgias, this book will surprise you.”—Tracy Borman, author of Queen of the Conqueror and Elizabeth’s Women

“The Borgias is a fascinating look into the lives of the notorious Italian Renaissance family and its reputation for womanizing, murder and corruption. Meyer turns centuries of accepted wisdom about the Borgias on its head, probing deep into contemporary documents and neglected histories to reveal some surprising truths. . . . The Borgias: The Hidden History is a gripping history of a tempestuous time and an infamous family.”—Shelf Awareness

“Meyer brings his considerable skills to another infamous Renaissance family, the Borgias [and] a fresh look into the machinations of power in Renaissance Italy. . . . [He] makes a convincing case that the Borgias have been given a raw deal.”—Historical Novels Review

“The mention of the Borgia family often conjures up images of a ruthless drive for power via assassination, serpentine plots, and sexual debauchery. This is partially owing to propaganda spread by contemporary rivals of the Borgias, nineteenth-century Renaissance historians, and even films and television shows. . . . [Meyer] convincingly looks past the mythology to present a more nuanced portrait of some members and their achievements. . . . [The] Borgias are treated with . . . evenhandedness in this well-researched and surprising study.”—Booklist

“Many accounts of the Borgias focus on the most scandalous stories about this powerful Italian Renaissance family. . . . Meyer argues that many of these salacious tales are untrue and the result of slander. Through a logical and thoughtful examination of sources . . . he shows that claims of corruption, poisoning, incest, and murder are untrue or greatly exaggerated.”—Library Journal

“The lively narrative makes a familiar but still incredibly complicated historical period easier to get a handle on.”—Waterloo Region Record

文摘

9780345526915|excerpt

Meyer / THE BORGIAS

1

A Most Improbable Pope

It is the third of April, and springtime is in full force.

We are in Rome, which in this year of 1455 is neither the glorious world capital it had been under the emperors of old nor the great city it will become once again in a few generations. Instead it is a dilapidated backwater of thirty or perhaps forty thousand souls.

At the Vatican, dominated by the thousand-year-old and slowly disintegrating St. Peter’s Basilica, the cardinals are assembling. They are doing so because ten days have passed since the death of Pope Nicholas V. Of “apoplexy,” the attending physicians have declared, thereby revealing that they haven’t the faintest idea of what it was that caused him to grow feebler week after week until finally, aged only fifty-seven, he himself announced that his end was at hand.

The death of this particular pontiff at this particular time is a deeply worrisome thing. As for the fact that the time has come to elect his successor—it is so snarled up in difficulties and dangers as to scarcely bear thinking about.

Officially and as usual, the first nine days after the pope’s death were reserved for the obsequies with which deceased pontiffs are launched into the afterlife: one requiem mass per day, each presided over by a different cardinal. But in fact, and inevitably, the days and the nights as well have been filled with backstairs politicking, mainly to see who can put together the most potent blocs of votes. In the midst of all this, Nicholas’s wizened little body has been sealed up in the traditional three coffins, one of cypress inside another of lead inside still another of fine-grained and polished elm. It was then laid to rest in the crypt under the basilica, a structure so alarmingly decrepit that in the last few years of the pope’s reign 2,500 cartloads of stone had been stripped from the Colosseum and hauled across the Tiber for use in shoring it up.

By the time the last Ite, missa est brought the last mass to an end, the windows of one wing of the pontifical palace were boarded up in the customary way. Austere little cells, each containing a cot, a stool, and a small table, have been hammered together inside. The fifteen available cardinals (six others are too far from Rome to attend) are now reporting for duty. As they file inside, the doors are bolted behind them. Guards are posted, and the conclave of 1455 is formally in session.

Deprived of natural light, the cardinals are dependent on candles and oil lamps for illumination. With no ventilation and wood fires the only source of morning warmth, the air they breathe will soon be foul. But conclaves are not supposed to be pleasant. Physical discomfort long ago proved its value. It encourages the princes of the Church to get on with their business, announce the results, and go home.

Every part of the process is governed by customs that have evolved over a millennium and a half. At various times the choosing of popes has been under the control of Roman emperors, Byzantine emperors, and Holy Roman emperors from beyond the Alps. Sometimes popes have been able to nominate their successors, and there have been periods when no one would dare take the throne without the approval of the clergy—even the people—of Rome. But in 1059 a papal decree conferred the right of election on the College of Cardinals. Eighty years later another decree gave that right to the cardinals exclusively, meaning that no further approvals were needed once the Sacred College had made its choice. Forty years after that, a two-thirds majority of votes cast became necessary for election.

With that, the pattern was set. Though there have been other changes—an attempt, for example, to force fast action by reducing the cardinals’ rations if they fail to reach a decision within three days and reducing them again if a pope has not been elected after five—the essential rules could hardly be simpler. Whoever can get the votes of ten of the men now locked together inside the palace will assume the full powers of the papacy from the moment of his election. He will do so even if the whole outside world disapproves.

Simple rules are no assurance of an easy outcome, however. Choosing a pope is always a complicated affair, because much is always at stake and so many competing forces invariably come into play. Things rarely go smoothly. As the cardinals settle into their cubicles and begin to talk among themselves, they know that this election is unlikely to be an exception.

Not that Nicholas has left them with a mess. To the contrary, he was in no way a bad or even a careless pope. By the standards of the time he was a good one. Anyone comparing him with his immediate predecessors might find reason to call him an almost great one. Raised in humble circumstances in northwestern Italy, he had risen in the Church purely on the basis of merit—first as one of the leading humanist scholars of his time, then through success as a diplomat. His election was a fluke; he became a cardinal only a few months before the conclave that made him pope, and it never could have happened if the most powerful factions in the College of Cardinals had not deadlocked. But the eight years of his reign proved to be rich in achievement and free of scandal. He contributed greatly to bringing peace and a measure of stability not only to Italy but to Germany as well, ended a last outbreak of schism, found honest ways to replenish the Vatican’s treasury, and resumed the oft-interrupted process of trying to restore the decayed city of Rome to its lost splendor.

Even more remarkably, he appointed only a single relative, a half-brother to the College of Cardinals and did nothing to enrich his kin. All in all, his reign has been an impressive step forward in the rebuilding of the papacy—in restoring its ancient importance and prestige. Whether this will continue or now come to a stop is likely to depend, everyone knows, on who is chosen to succeed him.

The problems facing the cardinals go much deeper than anything Nicholas did or failed to do. They are the residue of the century and a half of discord that preceded his reign: generation after generation of exile, of schism, of a deeply damaging struggle to decide whether the pope is the supreme head of the Church or subordinate to general councils. Some of the great questions are by now settled, or at least appear to be, but ugly memories are still fresh, deep wounds unhealed. Nicholas’s election came only four years after the return of the last exiled pope to Rome, and it was not until two years after his election that the last antipope abandoned his claim to the throne. A mere two years separate Nicholas’s death from the latest plot to overthrow papal rule and restore republican government in Rome. That he escaped unharmed does not mean that all danger has passed. That too is likely to depend, at least in part, on who takes his place.

If all Italy is at peace in 1455, this again is a departure from recent history and a fragile one. The peninsula last erupted in general war as recently as 1452, when Venice attacked Milan; Florence, Genoa, Bologna, and Mantua all came to Milan’s assistance; and Naples threw in with Venice. The pope, to his credit, kept Rome neutral, thereby leaving himself free to help broker a settlement and bring the belligerents together in what he called the Italian or Most Holy League. This league is without precedent in Italian history, a defensive alliance encompassing the whole peninsula, obliging longtime enemies to embrace each other as friends and aimed at establishing a balance of power stable enough to preserve the peace. It became effective only weeks before Nicholas’s death, when the troublesome king of Naples finally signed on, and was the crowning achievement of the pope’s career. It is supposed to remain in effect for twenty-five years, but the realities of Italian political life make its chances of doing so vanishingly small. The part that Nicholas played in making it all happen, coupled with his departure from the stage, adds to the sense that the conclave now in session matters more than most.

The existence of the league requires the most powerful princes in Italy to pledge to do things that they are unaccustomed to doing: respect existing frontiers, join forces to punish any state that breaks the peace, and work together to keep foreign powers out. It obliges the most ruthless and ambitious of these princes to abandon—to defer, anyway—long-cherished dreams of subduing their neighbors and seizing their domains. Few of them would have agreed to any such thing if not for one of the supreme political catastrophes of the late Middle Ages: the capture by the Ottoman Turks, just twenty-three months before Nicholas’s death, of the fabled city of Constantinople.

For eleven hundred years Constantinople had been the capital of the Eastern or Byzantine Empire, and incomparably richer and more important than Rome. It had also, for half a millennium, been the seat of the Orthodox Church. But after centuries of decline and generations of being dismantled piecemeal by the relentlessly expanding empire of the Turks, nothing remained but a pale shadow of what it had been at its zenith. Its end was tragic: after a siege of less than two months, a defense force of seven thousand troops was overwhelmed by eighty thousand Islamic invaders. This was followed by three days of horror, as Sultan Mehmed II (“Mehmed the Conqueror,” only twenty-one years old) rewarded his men by allowing them to pillage, rape, and kill at their pleasure. As many as fifty thousand of the proud old city’s inhabitants were put to the sword, and the survivors disappeared into the slave markets of the East. It was a world-changing event, and it chilled the blood of every Christian who understood its significance.

The West had no right to be shocked, actually; its leaders could not claim to have been caught off guard. They had stood by passively through all the years when the Turks drew ever closer to Constantinople. The city’s emperors had sent ever more desperate appeals for help, and Europe not only failed to respond but contributed to making collapse inevitable. If at midcentury the Turks controlled much of the Balkan peninsula and Hungary south of the Danube, this was not a new state of affairs: all of Bulgaria, along with much of Serbia, had been seized more than fifty years before. That Constantinople itself had become the Turks’ prime objective could not have been more obvious. When they cut off the Bosporus, the great waterway connecting Constantinople to the Black Sea and the world beyond, the city was caught in a stranglehold, its doom clearly imminent. Its last emperor—whose name, rather sadly, was Constantine, and who would die fighting when the Turks came swarming over his walls—got little from the West except bombastic words of encouragement and promises that meant nothing. Nicholas V made some effort to organize a rescue expedition, but nothing came of it. His failure to do more would be seen by many as the one disgrace of his reign.

In taking Constantinople the Turks gained not only a glorious new capital for their empire—the Hagia Sophia, one of the architectural wonders of classical times, was converted from a church to a mosque—not only one of the world’s most magnificent harbors, but a platform from which to threaten central and southern Europe. Venice, its fabulous wealth dependent on access to eastern markets, is the most threatened of the Italian states, but this too has long been the case, and Venice has been slow to take alarm. Its merchant princes grew up thinking of Constantinople as their principal commercial rival, not as a bulwark against Muslim aggression, and they took foolish satisfaction in its decline. They nursed hopes of taming the Turks and turning them into business partners. The folly of such thinking was not exposed until the Turks sank a Venetian ship trying to pass through the Bosporus, beheaded all the crewmen who had not drowned, and put the body of its captain on display after killing him by impalement. But by then, at least where Constantinople was concerned, it was already too late.

That Venice is not alone in its peril became clear when Sultan Mehmed, after taking Constantinople, added “Roman Caesar” to his list of titles. No one has mistaken this for a joke; if Constantinople could fall, so could Rome. And if Rome fell, who could say that Christian civilization was not doomed? It is questions like this, and the grimness of the only credible answers, that have caused the leading Italian powers to put aside their quarrels and come together in the Holy League.

These are the issues that hang over Italy, the Church, and Europe in April 1455, creating an urgent need for leadership. Human nature being what it is, however, they are not necessarily the issues that matter most to the cardinals sequestered in the Vatican. Domestic rivalries loom larger, and some at least of the cardinals can be depended upon to care more about getting an advantage over their rivals, or stopping their rivals from getting an advantage over them, than about anything as abstract as the fate of Western civilization. Coiled like a serpent at the heart of the conclave, capable of poisoning everything, is the blood feud that almost from time immemorial has kept Rome’s two greatest families at each other’s throats. Without the hatred of the Orsini for the Colonna and the Colonna for the Orsini, the seven Italians who make up the conclave’s largest national contingent could expect to have little difficulty recruiting the three additional votes needed to deliver the papacy to one of their own. Because of that hatred, the election of an Italian is going to be difficult at best.

This is no trivial matter. Since the return of the papal court from what is called the Babylonian Captivity, when for sixty-seven years it remained at Avignon in Provence and so completely under the thumb of the kings of France that seven consecutive popes were Frenchmen, there has been a return also to the assumption that popes should be Roman, and if not Roman then at least Italian. The people of the Eternal City take this idea seriously indeed. The cardinals know that the election of an outsider is likely to bring angry crowds into the streets, and that the election of someone from what the Romans regard as the barbarian world beyond the Alps would be certain to do so. Though the city has been fairly tranquil since the failure of the republican conspiracy of 1453, thanks largely to the pains taken by Nicholas V to deal even-handedly with the ever-jealous Orsini and Colonna and other baronial clans, not a great deal is ever needed to spark an explosion in Rome. The separation of the Italian cardinals into irreconcilable camps, and the consequent possibility of a non-Italian pope, are further causes of anxiety.

The Italians cannot be unified because of the presence of two of the Sacred College’s most formidable members, both of them Roman nobles, both in their mid-forties, and both able to draw on enormous reserves of political, financial, and even military power. Latino Orsini occupies the seat in the college that his family has held for so many centuries that its leaders regard it as theirs by right, as practically their personal property. Among the ornaments on his family tree are three Orsini popes, the first elected in 1191, and the second so notorious for corruption that Dante gave him a small speaking role as one of the damned souls in The Inferno. Latino need look no further than to his clan’s history for lessons in what a boon it can be to put a relative, or someone dependent on one’s relatives, on the papal throne. And for equally compelling examples of how badly things can go when that throne is occupied by an enemy—worst of all, from the Orsini perspective, by a Colonna or a friend of the Colonna.

Proud and potent though Latino is, he is outmatched by his most dangerous rival, Cardinal Prospero Colonna. A nephew of the Oddone Colonna who became Pope Martin V in 1417 and used his office to heap wealth, high office, and noble titles on his kinsmen, Prospero has had a colorful career. He was made a cardinal while still in his teens, was excommunicated after his uncle’s death changed the Colonna from Vatican insiders to undesirables, won his way back into favor, and then was very nearly elected himself. Through three tense days at the conclave of 1447, Prospero remained just two votes short of victory. His inability to get those two votes and the subsequent melting away of his support were due to the loyalty to the Orsini of several cardinals and the uneasiness felt by others because of Prospero’s notorious readiness to use violence in pursuing his objectives. It was this Orsini-versus-Colonna deadlock that led to the surprise election of the conclave’s newest member, the scholarly Tommaso Parentucelli, who had thus become the now-deceased Nicholas V.

The conditions that led to deadlock in 1447 are all in place in 1455. As the cardinals prepare to cast the first round of ballots, it becomes clear that the Italian Domenico Capranica is favored by a number of his colleagues. Objectively, this is an understandable, even a commendable, development. There is nothing objectionable about Capranica and much to recommend him. At fifty-five he is a seasoned senior churchman, having been a bishop for thirty years and a cardinal for more than twenty. He is also one of the Vatican’s leading diplomats and administrators, a humanist scholar of note, a champion of ecclesiastical reform, and so blameless in his personal life that historians of the early Renaissance will one day describe him as saintly.

By the measures that should matter most he is an exceptional candidate. No one could find good grounds for complaining of his election, and his colleagues like the fact that he has been one of them for nearly a generation; many of them feel that, because the late Nicholas had entered the Sacred College mere months before his election, he never developed a proper respect for its importance.

Capranica has a problem all the same, and it proves to be disabling. He began his career as secretary to the Colonna pope Martin V—had been chosen for the post because of his exceptional abilities and outstanding promise—and because of this the Orsini early classified him as an enemy and always treated him accordingly. Over the years he and the Orsini clashed so often and so seriously that there can be no hope of his election in any conclave over which Latino Orsini holds veto power.

Capranica’s cause being thus lost, Latino now puts forth his choice: Pietro Barbo, nephew of the Pope Eugenius IV who had died in 1447 (and who himself had been the nephew of a still earlier pope). Barbo is a fifteen-year veteran of the college in spite of being only thirty-eight years old, and though not as distinguished as Capranica, he is in no way unworthy of consideration. He has the support not only of the Orsini but of Venice and the king of Naples as well. But he too has no chance, and for reasons unrelated to anything he himself has ever said or done. The problem is his late uncle. When Eugenius made Barbo a cardinal at age twenty-three, he did so in Florence, and he was living in Florence because six years earlier he had fled Rome for his life, and his flight from Rome had become necessary when he tried to break the power of the Colonna and instead was overpowered.

The result was humiliation. Three years after his election Eugenius found himself disguised as a monk and floating downstream in a Tiber barge, cowering under a shield as wrathful Romans shouted their contempt and hurled stones, sticks, and rubbish down on him from the banks above. He found refuge in Florence, which welcomed him because its dominant family, the Medici, was closely affiliated with the Orsini, who were always happy to embrace an enemy of the Colonna.

Rome was ultimately retaken by force, not by Eugenius himself but by a commander of the papal army named Giovanni Vitelleschi, who was both a cardinal and one of the most savagely aggressive soldiers of the age. The leader of Rome’s short-lived, Colonna-sponsored republic was dismembered alive by men wielding red-hot tongs, and the city was put under a military occupation designed to make resistance impossible and life intolerable for any Colonna foolish enough to remain. The provinces belonging to the papacy and known as the Papal States were ravaged as well, even the churches of towns disloyal to the exiled pope were razed, and the city of Palestrina, seat of one of the Colonna family’s most powerful branches, was obliterated.

Pietro Barbo had nothing to do with any of this—it is unclear whether even his uncle the pope intended or approved the atrocities committed in his name—but in the eyes of the Colonna he is fatally tainted, absolutely and forever unworthy of trust. If in 1455 Prospero Colonna no longer has sufficient clout to stand as a credible candidate himself, he certainly remains capable of blocking the election of anyone suspected of being a danger to his clan. He is helped by Barbo’s relative youth. Not without reason, cardinals tend to think it unwise to bestow the crown on someone who might possibly wear it for twenty or thirty years. In Barbo’s case a forty-year reign would not be inconceivable.

With Capranica and Barbo eliminated, clearly a compromise is needed, one that Latino and Prospero will accept. Days are passing, and as the cardinals look about them for a solution, several find their attention fixing on an ecclesiastical anomaly. This is Basilios Bessarion, who with his compatriot Isidore of Kiev is one of two Greeks present at the conclave. Both began their careers in the Orthodox Church, rose high in the hierarchy at Constantinople, and in 1434 were appointed delegates to the Roman Church’s Council of Basel, where they showed themselves to be strongly in favor of ending the centuries-old split between the Eastern and Western rites. In 1439, when the council was meeting in Florence, Bessarion and Isidore delighted the papal court and became traitors in the eyes of their Orthodox brethren by defecting to Rome. In short order they were made cardinals. Over the next decade and a half Bessarion won a reputation as one of Europe’s leading humanists and promoters of the new learning, and as a man of solid competence and impeccable moral character. Also in his favor, in the opinion of many cardinals, are the appreciation of the Turkish threat that his Eastern origins have given him and his insistence that the West must respond forcefully.

But he too has no chance of election. The conclave’s French members, no longer keeping silent because what is under discussion is no longer a strictly Italian quarrel, take the lead in complaining that Bessarion is an alien. They make much of the fact that, contrary to the conventions of the Sacred College, he continues, in the Byzantine fashion, to wear a long beard. Even those cardinals who most admire Bessarion find it necessary to agree that expecting him to rule Rome and its Church could end in nothing but calamity.

So . . . some other compromise has to be found. The cardinals, frustrated and weary and wanting to be set free, find it quickly. Find him quickly. The desire to be done with this tiresome business awakens them at last to the fact that there is in their midst a man of whom no one has a bad word to say. A man who, if not a champion of the new humanism in the manner of Capranica or Bessarion or Pope Nicholas, is an esteemed scholar nevertheless, with two doctorates in law and an international reputation as an authority on the subject.

A good man, untouched by scandal and known to all Rome for his sponsorship of hospitals, his generosity to the elderly and the poor, and the simplicity of his life.

A statesman too, with an impressive career behind him and decades spent at the right hand of one of the greatest kings in Europe.

A peacemaker of the first order, a key player in bringing the Western Schism to an end and settling a long conflict between Naples and Rome.

Known to be loyal to popes rather than councils, and to understand the Turkish threat.

Not greedy—not even ambitious.

And, what matters more in this deadlocked conclave, free of politics: unaffiliated with any of the Sacred College’s factions after ten years as a member, so detached from the intrigues of the papal court that no one—no Orsini, no Colonna, no anyone—has reason to regard him with distrust.

And finally—what’s best of all, the clincher—seventy-six years old and in declining health. It is inconceivable that he will live much longer. This makes him perfect.

And so when Cardinal Bessarion rises to his feet and declares in solemn tones that he is giving his vote to Alonso Borgia, his compeers all but fall over themselves in their haste to do the same. They do so with joyful relief, confident that they are settling on a man who will reign benignly, passively, and above all briefly, soon departing for the here- after having distressed no one and changed nothing.

Little do they know.

著者簡介

G. J. Meyer is the author of two popular works of history, The Tudors and A World Undone: The Story of the Great War, as well as Executive Blues and The Memphis Murders. He received an M.A. from the University of Minnesota, where he was a Woodrow Wilson Fellow, and later was awarded Harvard University’s Nieman Fellowship in Journalism. He has taught at colleges in Des Moines, St. Louis, and New York, and now lives in Wiltshire, England.

圖書目錄

讀後感

評分

評分

評分

評分

用戶評價

相關圖書

本站所有內容均為互聯網搜索引擎提供的公開搜索信息,本站不存儲任何數據與內容,任何內容與數據均與本站無關,如有需要請聯繫相關搜索引擎包括但不限於百度,google,bing,sogou 等

© 2025 book.quotespace.org All Rights Reserved. 小美書屋 版权所有