A History of Western Music pdf epub mobi txt 电子书 下载 2026

- 音乐

- MusicHistory

- 西方音乐史

- 历史

- music

- 艺术史

- history

- 英文原版

- 音乐史

- 西方音乐

- 古典音乐

- 音乐学

- 西方文化

- 历史文献

- 音乐理论

- 艺术史

- 西方文明

- 音乐教育

具体描述

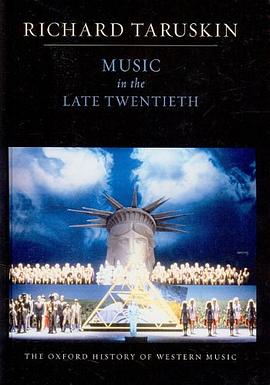

The Eighth Edition of A History of Western Music is a vivid, accessible, and richly contextual view of music in Western culture. Building on his monumental revision of the Seventh Edition, Peter Burkholder has refined an inspired narrative for a new generation of students, placing people at the center of the story. The narrative of A History of Western Music naturally focuses on the musical works, styles, genres, and ideas that have proven most influential, enduring, and significant—but it also encompasses a wide range of music, from religious to secular, from serious to humorous, from art music to popular music, and from Europe to the Americas. With a six-part structure emphasizing the music’s reception and continued influence, Burkholder’s narrative establishes a social and historical context for each repertoire to reveal its legacy and its significance today.

作者简介

目录信息

读后感

ps:读的是 A history of Western Music (sixth edition),中英文版同时进行的。英文版的有些晕,知识点也记得不是很清晰;中文版的扫读很快,为获得知识而阅读。 这一次是从后往前读的。一直觉得自己对20世纪之后的音乐掌握的不好,主观客观都有原因。 在面对诸多只见其名...

评分I bought it 10 years ago, maybe 11. I used it for my preparation to get in to the Musicology department of the Music Academy. I didn't get accept. And I fled to America. I brought a few books with me, this one is among them. Even though after 10 years, I...

评分买这本书的时候也是因为要考音乐学。不过那时候还不知道自己要考哪所音乐学院。 三大音乐史版块最讨厌的就是中国近现代音乐史,当然这只是考学时的偏颇。现在已然知道,这都是当时近现代音乐史考书害的!!!! 西方音乐史的书我家有好多,都读过,而且伴随我的音乐学院学历...

评分ps:读的是 A history of Western Music (sixth edition),中英文版同时进行的。英文版的有些晕,知识点也记得不是很清晰;中文版的扫读很快,为获得知识而阅读。 这一次是从后往前读的。一直觉得自己对20世纪之后的音乐掌握的不好,主观客观都有原因。 在面对诸多只见其名...

评分I bought it 10 years ago, maybe 11. I used it for my preparation to get in to the Musicology department of the Music Academy. I didn't get accept. And I fled to America. I brought a few books with me, this one is among them. Even though after 10 years, I...

用户评价

这本书《西方音乐史》为我开启了一扇通往音乐殿堂的大门。作者以其流畅的文笔和深厚的学养,将西方音乐的发展历程娓娓道来。我尤其欣赏他对音乐史中各个关键转折点的细致分析,例如从中世纪的教会音乐到文艺复兴时期世俗音乐的兴起,再到巴洛克时期音乐的繁复与华丽。书中对作曲家及其作品的介绍,不仅包含对其艺术风格的分析,还穿插了他们的生平经历和时代背景,使得音乐家的形象更加鲜活。我曾对古典主义时期的音乐风格感到有些单一,但通过本书的介绍,我认识到莫扎特的优雅、海顿的创新以及贝多芬的革命性,它们共同构成了古典主义的丰富内涵。浪漫主义时期,音乐情感的释放与个人表达的凸显,让我深深着迷。肖邦的钢琴作品,李斯特的浪漫主义精神,以及瓦格纳的乐剧,都给我留下了深刻的印象。作者对这些作品的解读,不仅分析了其音乐结构,更挖掘了其背后蕴含的情感力量和哲学思考。此外,本书对印象主义、表现主义以及现代音乐的介绍,也拓宽了我的音乐视野,让我开始欣赏那些具有实验性和前卫性的作品。

评分阅读《西方音乐史》的过程,就像是在一个巨大的音乐画廊中漫步,每一件展品都诉说着一段动人的故事。作者的文笔优美且富有洞察力,他能够精准地捕捉到不同音乐风格的精髓,并将其生动地呈现在读者面前。我特别喜欢他对音乐的感知和联想,例如用“明亮的阳光”来形容海顿的音乐,用“深邃的星空”来形容马勒的交响曲,这些比喻非常形象,能够帮助我更好地进入音乐的情境。书中对从格里高利圣咏到十四、十五世纪的复调音乐,再到文艺复兴时期“新音乐”的演进,都做了详尽的梳理。我曾经对奥兰多·德·拉苏斯和帕莱斯特里纳的作品感到有些陌生,但通过这本书的介绍,我开始欣赏到他们音乐中那种严谨的对位技巧和丰富的情感表达。古典主义时期,莫扎特的歌剧和交响乐,海顿的弦乐四重奏,都是我反复聆听的对象,而这本书为我提供了更深入的理解角度。从奏鸣曲式的结构解析,到主题发展的手法,再到音乐的清晰性和平衡感,都得到了细致的阐释。浪漫主义时期,肖邦的钢琴作品,李斯特的钢琴炫技,瓦格纳的乐剧,以及勃拉姆斯的深沉思考,都给我留下了深刻的印象。作者在分析这些作品时,总是能联系到作曲家当时的心境和历史背景,让音乐的解读更加富有层次。

评分《西方音乐史》是一部引人入胜的音乐探索之旅。作者以其渊博的学识和细腻的文笔,为我揭示了西方音乐数千年的演变轨迹。我非常赞赏他对音乐理论的深入浅出,能够将复杂的概念转化为易于理解的叙述。从古希腊的音乐哲学,到中世纪的格里高利圣咏,再到文艺复兴时期复调音乐的巅峰,每一段历史时期都栩栩如生。我尤其被作者对音乐形式演变的讲解所吸引,例如奏鸣曲式的起源和发展,以及赋格在巴洛克时期的重要地位。书中对歌剧的介绍也让我着迷,从早期歌剧的戏剧性到莫扎特歌剧的完美结合,再到瓦格纳的宏大乐剧,作者都做了精彩的梳理。他不仅关注了音乐本身,还深入探讨了音乐在社会、文化和技术发展中的作用。例如,他对乐器革新如何推动音乐创作的阐述,就让我对音乐的物质基础有了更深刻的认识。我曾经对某些现代音乐作品感到难以理解,但通过这本书对十二音体系、序列音乐、偶然音乐等概念的介绍,我开始理解了这些音乐形式的探索性和其在音乐史上的价值。作者的讲解清晰而富有逻辑,能够引导读者逐步理解那些看似晦涩的音乐理论。

评分《西方音乐史》这本书带给我的不仅是知识的增长,更是一种心灵的洗礼。它让我重新审视了音乐在人类文明中的地位,以及音乐如何反映和塑造着人类的情感与思想。从古罗马时期音乐的社会功能,到中世纪教会音乐的神秘庄严,再到文艺复兴时期人文主义对音乐创作的影响,每一个时代都在书中被赋予了独特的色彩。我特别着迷于作者对音乐形式的分析,比如奏鸣曲式的起源和发展,赋格的逻辑结构,以及歌剧的戏剧性表达。他不仅仅是列举这些形式,更重要的是解释了它们是如何在历史进程中演变,又是如何被不同的作曲家赋予新的生命。对于像莫扎特和贝多芬这样的巨匠,作者的分析尤其深刻,他不仅仅赞美他们的天才,更深入地探讨了他们的创作理念、艺术追求以及他们所处的时代如何影响了他们的音乐。读到贝多芬的晚期作品时,我仿佛能感受到他身处逆境时那种不屈不挠的精神,这种对音乐背后情感力量的挖掘,让我对音乐产生了更深层次的共鸣。书中对印象主义和现代音乐的介绍,也让我突破了以往对“好听”或“不好听”的简单评判,开始欣赏音乐中更多的可能性和实验性。例如,作者对斯特拉文斯基《春之祭》的分析,让我理解了这部作品为何会在首演时引起如此大的轰动,以及它在音乐史上的革命性意义。这本书也促使我去探索更多相关的音乐作品,每一次聆听都仿佛与书中描绘的音乐世界进行了更深入的对话。

评分我必须说,《西方音乐史》这本书让我对音乐的理解提升到了一个全新的高度。它并非仅仅是一部音乐作品的编年史,更是一部关于音乐如何与人类社会、文化、思想紧密相连的精彩叙事。作者的功力体现在他能够将复杂的音乐理论和历史事件,以一种引人入胜且清晰易懂的方式呈现出来。我尤其欣赏他对不同音乐时期过渡阶段的细致描绘,例如从巴洛克到古典主义的转变,是如何受到哲学启蒙运动思想的影响,又是如何体现在音乐形式和表达上的变化。书中对教会音乐在传播和发展中的作用,以及世俗音乐如何逐渐兴起并占据重要地位的描述,让我对音乐的社会功能有了更全面的认识。对于歌剧的起源和发展,作者的讲解更是生动有趣,他不仅介绍了早期歌剧的特点,还深入分析了蒙特威尔第、莫扎特、威尔第等作曲家如何将音乐与戏剧完美结合,创造出扣人心弦的艺术体验。我印象最深刻的是,作者在介绍某一个作曲家时,不仅会分析他的代表作品,还会穿插讲述他的生活经历、创作灵感以及他与同时代人的交往,这使得音乐家形象更加立体丰满。例如,在讲述肖邦时,作者描绘了他作为波兰流亡者的忧郁与坚韧,以及他在巴黎的艺术圈中的地位,这让我能更好地理解他音乐中那份细腻的情感和民族情怀。这本书的深度和广度都令人惊叹,它不仅适合音乐专业人士,也对任何热爱音乐的普通读者来说,都是一本不可多得的宝藏。

评分这本《西方音乐史》真是一次令人惊叹的音乐之旅!从古希腊的调式到21世纪的先锋实验,作者以其深厚的学识和引人入胜的笔触,为我打开了一个宏伟而复杂的音乐世界。读这本书,我感觉自己就像一位探险家,穿梭于历史的长河中,亲历每一个重要音乐时期的诞生与演变。书中对中世纪格里高利圣咏的描绘,那种虔诚而宁静的氛围仿佛把我带进了古老的教堂;文艺复兴时期复调音乐的精妙结构,那些交织的旋律如同精雕细琢的艺术品,展现了人类智慧的结晶。特别是巴洛克时期,我完全被维瓦尔第的《四季》和巴赫的赋格所震撼,它们不仅是音乐技巧的极致展现,更是情感的深邃表达。莫扎特的优雅与贝多芬的磅礴,海顿的平衡与勃拉姆斯的厚重,肖邦的细腻与李斯特的奔放,每一个作曲家都栩栩如生,他们的音乐理念和创作风格被剖析得淋漓尽致。书中对浪漫主义时期民族音乐的兴起,如德沃夏克的斯拉夫舞曲,也让我对音乐与民族文化之间的紧密联系有了更深刻的理解。从印象主义的色彩斑斓到十二音体系的理性探索,再到现代音乐的多元实验,作者都给予了详尽而易懂的阐释。这本书不仅仅是关于作曲家和作品的罗列,它更深入地探讨了音乐在社会、文化、宗教和哲学等各个层面的影响,揭示了音乐作为人类精神表达载体的重要性。我尤其欣赏作者在介绍不同音乐时期时,会将其置于当时的历史背景和社会环境中进行分析,这使得音乐的发展脉络更加清晰,也更能理解音乐创作背后的驱动力。例如,在谈到中世纪音乐时,作者详细介绍了修道院在音乐传播和发展中的作用;而在描述宗教改革对音乐的影响时,马丁·路德的宗教音乐改革被赋予了重要的历史意义。这些细节的加入,让这本书的阅读体验更加立体和丰富。

评分这是一本让我从心底里感到满足的书。《西方音乐史》不仅是一本记录历史的著作,更是一本能够激发思考和共鸣的艺术指南。作者的文字如同涓涓细流,缓缓地流淌进我的内心,让我沉醉于西方音乐的迷人世界。我尤其欣赏他对不同音乐时期之间联系和过渡的描绘,例如从古希腊的音乐理念到中世纪教会音乐的传承,再到文艺复兴时期音乐的复苏与创新,这些转折点都被作者描绘得清晰而有逻辑。书中对巴洛克时期音乐的讲解,特别是对巴赫的复调音乐和维瓦尔第的协奏曲的分析,让我体会到了那个时代音乐的辉煌与复杂。古典主义时期,莫扎特的优雅与纯净,海顿的秩序与平衡,以及贝多芬的英雄气质与创新精神,都在作者的笔下栩栩如生。我尤其对作者对贝多芬后期作品的解读印象深刻,那是一种超越苦难的宁静与智慧。浪漫主义时期,音乐的情感表达变得更加自由和强烈,肖邦的钢琴作品,舒曼的歌曲,勃拉姆斯的交响曲,都展现了那个时代艺术家内心的激情与思考。书中对民族乐派的介绍,如斯美塔那和德沃夏克的音乐,也让我看到了音乐与民族文化之间的紧密联系。

评分《西方音乐史》这本书,让我对音乐的认识不再停留在表面的旋律和节奏,而是深入到了音乐的灵魂深处。作者以其严谨的学术态度和卓越的叙事能力,为我勾勒出了一幅宏伟壮丽的西方音乐发展画卷。从古希腊的音乐理论,到中世纪的教会音乐,再到文艺复兴时期的人文主义思潮对音乐的影响,每一个章节都充满了智慧的光芒。我特别被作者对音乐形式演变的分析所吸引,例如奏鸣曲式从古典主义时期的成熟,到浪漫主义时期如何被更自由和多样化的处理。书中对歌剧的介绍也让我着迷,从早期的卡默拉塔到威尔第和瓦格纳的宏大乐剧,作者都做了精彩的梳理。他不仅关注了音乐本身,还深入探讨了音乐在历史进程中的社会功能、文化意义以及技术发展对其产生的影响。例如,他对乐器革新如何推动音乐创作的阐述,就让我对乐器的发展有了更深刻的认识。我曾经对某些现代音乐作品感到难以接受,但通过这本书对十二音体系、序列音乐、偶然音乐等概念的介绍,我开始理解了这些音乐形式的探索性和其在音乐史上的价值。作者的讲解清晰而富有逻辑,能够引导读者逐步理解那些看似晦涩的音乐理论。

评分这是一本真正能够激发你对音乐产生无限热情的著作。它不是那种枯燥的学术论文集,而是充满生命力的叙事。作者的写作风格非常平易近人,即使你对古典音乐知之甚少,也能轻松地跟随他的思路进行探索。我尤其喜欢他如何将抽象的音乐概念具象化,通过生动的语言和恰当的比喻,让我能够“听见”音乐的色彩和情感。例如,在描述德彪西的音乐时,他用“模糊的色彩”和“朦胧的光影”来形容,让我立刻联想到印象派绘画,这种跨领域的类比非常巧妙。书中对每个时期的音乐风格演变和代表性作曲家的介绍都非常有条理,从早期复调到后来的主调音乐,从古典主义的清晰结构到浪漫主义的自由奔放,每一个转变都被解释得合情合理。我曾经对某些音乐家感到困惑,但读了这本书后,很多原本模糊的概念都变得清晰起来。比如,对于勋伯格的十二音体系,我一直觉得难以理解,但作者通过详细的分析和历史的铺垫,让我看到了这个体系的逻辑性和它在音乐发展史上的重要性。此外,书中还涉及了许多非欧洲中心的音乐传统,虽然篇幅可能不如欧洲音乐那么详尽,但其包容性让我印象深刻。作者并没有将音乐史仅仅局限于几个“大师”,而是关注了音乐在更广泛社会语境下的发展,包括音乐教育、乐器发展以及观众的变化等等。这些方面的探讨,让音乐史不再是遥远的过去,而是与我们的生活息息相关。我强烈推荐这本书给所有对音乐有好奇心的人,它会打开你的耳朵,让你听到更多,理解更深。

评分这本书《西方音乐史》是一次让我大开眼界的阅读体验。它不仅仅是音乐知识的堆积,更是一种艺术品鉴能力的培养。作者的叙述方式非常流畅,他能够将庞杂的音乐史梳理得井井有条,让你在阅读中能够清晰地把握音乐发展的脉络。我印象最深刻的是,他对于每个音乐时期及其代表性作曲家的分析,都充满了独到的见解。例如,在介绍巴洛克时期时,他不仅谈到了巴赫、亨德尔和维瓦尔第,还深入分析了康塔塔、赋格、协奏曲等音乐体裁的发展。我曾经对巴洛克音乐中那种繁复的装饰和对位技巧感到有些难以理解,但通过书中对赋格的细致讲解,我开始领略到其内在的逻辑性和艺术魅力。古典主义时期,莫扎特的音乐以其优雅和完美著称,而贝多芬则以其英雄主义和创新精神引领了时代。作者对这两位巨匠的对比分析,让我更加深刻地理解了他们各自的音乐语言和艺术贡献。浪漫主义时期,音乐的情感表达变得更加自由和奔放,肖邦的钢琴诗篇,舒伯特的艺术歌曲,门德尔松的旋律优美,都展现了这一时期的多样性。我尤其喜欢作者对勃拉姆斯音乐的解读,他将其描述为“古典传统的继承者”,并分析了其音乐中蕴含的深刻哲思。

评分除了太贵了点。。内容还是不错的

评分除了太贵了点。。内容还是不错的

评分两天内卖出的第二本书。不大愿卖。不少有意思的段落和笔记,部分如下。学到1750,期末论文关于巴赫《赋格的艺术》。关注:古希腊音乐理论的发展和复兴; M.L.West。 p.316 It is sometimes not the originator of an idea, but the first person to show its full potential, who gives it a permanent place in human history. So it appears with opera, whose first widely renowned composer was not Peri or Caccini but Claudio Monteverdi. (原评*:originator 无寻; recognition) p.310 ...opera might never have emerged without the interest of humanist scholars, poets, musicians, and patrons in reviving Greek tragedy. They hoped to generate the ethical effects of ancient music in Greece by creating modern works with equal emotional power...In this sense, opera fulfilled a profoundly humanist agenda, a parallel in dramatic music to the emulation of ancient Greek sculpture and architecture. Renaissance scholars disagreed among themselves about the role of music in ancient tragedy...After reading in Greek almost every ancient work on music that survived, he (Girolamo Mei, 1519-1594) concluded that Greek music consisted of a single melody, sung by a soloist or chorus, with or without accompaniment. This melody could evoke powerful emotional effects in the listener through the natural expressiveness of vocal registers, rising and falling pitch, and changing rhythms and tempo. p.39 Boethius (ca.480-ca.524) was the most revered authority on music in the Middle Ages...Music for Boethius is a science of numbers, and numerical ratios and proportions determine intervals, consonances, scales and tuning. Boethius compiled the book from Greek sources, mainly a lost treatise by Nicomachus and the first book of Ptolemy's Harmonics...(Figure 2.10) the three types of music Boethius described: at the top, musica mundana, the mathematical order of the universe; in the middle, musica humana, the harmony of the human body and soul; and on the bottom, musica instrumentalis, audible music (Lebrecht Music & Arts)...Boethius emphasized the influence of music on character...He valued music primarily as an object of knowledge, not a practical pursuit. For him music was the study of high and low sounds by means of reason and the senses; the philosopher who used reason to make judgments about music was the true musician, not the singer or someone who made up songs by instinct. p.10-11 The aulos was a pipe typically played in pairs...used in the worship of Dionysus, god of fertility and wine; Lyres usually had seven strings and were strummed with a plectrum, or pick...The lyre was associated with Apollo; The kithara was a large lyre, used especially for processions and sacred ceremonies and in the theater... the Greeks, despite having a well-developed form of notation by the fourth century B.C.E., primarily learned music by ear; they played and sang from memory or improvised using conventions and formulas. p.12 From the sixth century B.C.E. or earlier, the aulos and kithara were played as solo instruments. Sakadas of Argos won the prize for aulos playing at the Pythian Games...performing the Pythic Nomos, a virtuoso composition portraying Apollo's victory over the serpent Python; one writer attributes the piece to Sakadas, making him the earliest composer of instrumental music whose name we know. (Figure 1.9: Kitharode singing to his own accompaniment on the kithara, with his head tilted back: *迁:常给神?或显盲弹) p.12 There were two principal kinds of writings on music: (1) philosophical doctrines on the nature of music, its effects, and its proper uses [most influential: by Plato in his Republic and Timaeus and by Aristotle in his Politics]; and (2) systematic descriptions of the materials of music, what we now call music theory [evolved continually from the time of its founder, Pythagoras, to Aristides Quintilianus, its last important writer]. p.13 Music as a performing art was called melos...Melos could denote an instrumental melody alone or a song with text, and "perfect melos" was melody, text, and stylized dance movement conceived as a whole. For the Greeks, music and poetry were nearly synonymous..."Lyric" poetry meant poetry sung to the lyre; "tragedy" incorporates the noun ode, "the art of singing." (*: spatial-temporal) p.13 For Pythagoras and his followers, numbers were the key to the universe, and music was inseparable from numbers. Rhythms were ordered by numbers, because each note was some multiple of a primary duration. Pythagoras was credited with discovering that the octave, fifth, and fourth, long recognized as consonances, are also related to numbers. These intervals are generated by the simplest possible ratio: for example, when a string is divided, segments whose lengths are in the ratio 2:1 sound an octave, 3:2 a fifth, and 4:3 a fourth. p.13 Because musical sounds and rhythms were ordered by numbers, they were thought to exemplify the general concept of harmonia, the unification of parts in an orderly whole...Greek writers perceived music as a reflection of the order of the universe. p.13-14 Greek writers believed that music could affect ethos, one's ethical character of way of being and behaving...Through the doctrine of imitation outlined in his Politics, Aristotle described how music affected behavior: music that imitated a certain ethos aroused that ethos in the listener. The imitation of an ethos was accomplished partly through the choice of harmonia, in the sense of a scale type or style of melody. p.14-15 Plato and Aristotle both argued that education should stress gymnastics (to discipline the body) and music (to discipline the mind). In his Republic, Plato insisted that the two must be balanced, because too much music made one weak and irritable while too much gymnastics made one uncivilized, violent, and ignorant. Only certain music was suitable, since habitual listening to music that roused ignoble states of mind distorted a person's character. Those being trained to govern should avoid melodies expressing softness and indolence. Plato endorsed two harmoniai--the Dorian and Phrygian, because they fostered temperance and courage--and excluded others...Aristotle, in his Politics, was less restrictive than Plato. He held that music could be used for enjoyment as well as education and that negative emotions such as pity and fear could be purged by inducing them through music and drama. However, he felt that sons of free citizens should not seek professional training or instruments or aspire to the virtuosity shown by performers in competitions since it was menial and vulgar to play solely for the pleasure of others rather than for one's own improvement. p.9 India and China developed independently from Mesopotamia and were probably too distant to affect Greek or European music. Surviving sources that shed light on Egyptian musical traditions are especially rich...Archaeological remains and images that relate to music are relatively scant for ancient Israel, but music in religious observances is described in the Bible.

评分除了太贵了点。。内容还是不错的

评分除了太贵了点。。内容还是不错的

相关图书

本站所有内容均为互联网搜索引擎提供的公开搜索信息,本站不存储任何数据与内容,任何内容与数据均与本站无关,如有需要请联系相关搜索引擎包括但不限于百度,google,bing,sogou 等

© 2026 book.quotespace.org All Rights Reserved. 小美书屋 版权所有