具体描述

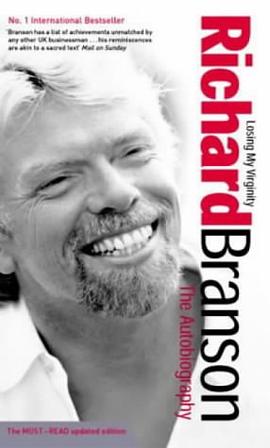

Book Description

The FBI that Louis Freeh took over in the summer of 1993 was still reeling from the bloody standoff at Ruby Ridge and the conflagration at the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas. Unpopular, underfunded, and understaffed, the Bureau was also creeping along in the technological Dark Ages. For eight years - the second-longest tenure of any director since J. Edgar Hoover - Freeh would fight tooth and nail to turn the FBI around.

Maybe because he had once been an FBI agent himself, Freeh was the most hands-on director in Bureau history. He didn't sit in Washington; he was there, on the ground, at some of the most high-profile crime sites the Bureau has ever taken on. In these pages, he takes readers with him: to Khobar Towers in the Saudi desert, where the dust is still settling on the remains of nineteen murdered U.S. servicemen; to Oklahoma City, where shredded children's toys lie scattered amid the ruins of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building; and to places far and wide.

This is Louis Freeh's entire story - from his Catholic upbringing in suburban New Jersey to law school, the FBI training academy, his career as an assistant U.S. attorney and as a federal judge, and finally his eight years as the nation's top cop. We see him at work as a field agent, using wiretaps and even going undercover to take down the corrupt leadership of the longshoremen's union. My FBI also takes readers through Freeh's prosecutorial crusades - from the Donnie Brasco case, which took down the Bonanno crime family, to internationally coordinated attacks on the Sicilian mob.

My FBI takes readers inside law enforcement at the highest level. It captures Freeh's showdown with Bill Clinton and also shows how a dedicated, apolitical professional faced down the absurdities of Beltway politics and repeatedly put himself on the line for a mission few others in Washington took seriously before September 11: ensuring the safety of the American people.

Louis Freeh led the Federal Bureau of Investigation from 1993 to 2001, through some of the most tumultuous times in its long history. Bill Clinton called Freeh a "law enforcement legend" when he nominated him as FBI Director. Unfortunately, the good feelings would not last. When Clinton later called that appointment the worst one he had made as president, Freeh considered it "a badge of honour." The FBI that Freeh took over was still reeling from the bloody standoff at Ruby Ridge and the conflagration that ended the siege at the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas. Unpopular, under-funded and understaffed, the Bureau was also creeping along in the technological Dark Ages. For eight years-the second longest tenure of any Director since J. Edgar Hoover - Freeh would fight tooth and nail to turn the FBI around, including going toe-to-toe with his boss during the scandal-plagued '90s, when Freeh defended his agency from political interference and worked to protect America from the growing threat of terrorism. This is Freeh's entire story, from his Catholic upbringing in New Jersey to law school, the FBI training academy, his career as a U.5. District attorney and as a federal judge, and finally his eight years as the nation's top cop. With a frank, clear-eyed, and realistic view, Freeh delivers the definitive account of American law enforcement in the run-up to September 11.

From Publishers Weekly

Freeh defends his performance as FBI director (1993-2001) and retaliates against Richard A. Clarke's Against All Enemies and Bill Clinton's My Life in this smooth memoir, written with the help of Means. "I spent most of the almost eight years as director investigating the man who had appointed me," Freeh declares on the book's first page, but readers expecting juicy revelations about those investigations are going to be disappointed. Freeh goes into fascinating detail when describing the FBI's work on the 1996 Khobar Towers bombing in Saudi Arabia-the most damning thing he has to say about Clinton is that Clinton didn't push for the prosecution of the bombers. Freeh's recounting of his work as an FBI agent in 1970s, when his team helped eviscerate the power of the Italian mafia in New York, is similarly generous with details. And his accounts of his childhood in New Jersey and his years working his way through Rutgers are also engaging. Freeh argues convincingly against the establishment of a separate Domestic Intelligence Service, for the FBI's use of international agents and for a major investment into the Bureau's technological capacity-it's horrifying to realize that the agency has less computer power than any of America's major enemies. In a few pages of near end of the book, Freeh lambastes Clarke, calling him a "self-appointed Paul Revere" and a "second-tier player." He also accuses Clarke of deception, alleging that Clarke lied or distorted information in five places, including Clarke's assertion that Freeh is a member of Opus Dei. If corroborated, these accusations may deal a serious blow Clarke's reputation. When it comes to the Clinton investigations, however, Freeh doesn't really deliver anything new. And his explanations for the rift between them come off as disingenuous. "Maybe I was, in Clinton's eyes, too much the altar boy," Freeh muses on page 17. More than two hundred pages later, he reveals that he snubbed the President's first two collegial gestures, and elsewhere Freeh drops references to his close friendship with H.W. Bush, who worked as director of the CIA before he was president and after whom Freeh names the FBI's new command center in 1999. "We had differences of temperament," Freeh acknowledges about Clinton. His book would have been stronger if he acknowledged more directly that he and Clinton had differences of politics, too. After all, it's to Clinton's credit that he appointed Freeh despite those differences, and to Freeh's credit that he didn't allow them to hamper his excellent performance on the Oklahoma bombing and Robert Hanssen cases, among others.

From The Washington Post's Book World /washingtonpost.com

For nearly a dozen years, Louis J. Freeh has been pointedly silent about the man who appointed him director of the FBI. That moratorium ends officially and loudly with the publication of Freeh's My FBI, a scorching account of his relationship with Bill Clinton and of leading the bureau at a time when, as Freeh writes, the president's "scandals . . . never ended." To understand the depth of Freeh's antipathy, consider this one anecdote: Sometime after he resigned in 2001, Freeh ran into the former White House counsel who had recommended Freeh for the job. The lawyer reported that Clinton had just complained to him that the worst advice the lawyer ever gave him was to appoint Freeh. "I wear it as a badge of honor," Freeh writes. And that's just the second chapter.

How did it come to this? A president's relationship with an FBI director should be a mixture of hands-off and hands-on. Unlike cabinet members, who serve at the pleasure of a president, directors are now given 10-year terms -- in part to avoid another 48-year reign like that of J. Edgar Hoover, and in part to provide insulation from political pressure. A potentially secret police force constitutes a great opportunity for abuse by presidents and a threat to be used against them. But even if an FBI director cannot expect to be best friends with the president, he should, as Freeh writes, "be able to go directly to the president, sit down with him and say You should know about this." In Freeh and Clinton's case, there were vital issues to discuss and collaborate on. But the problem for Freeh was that he never could get to those hands-on moments. "There was always some new investigation brewing, some new calamity bubbling just below the headlines ." By the time Freeh resigned, he had met with Clinton at most three times.

My FBI is no ordinary Washington memoir. To be sure, Freeh tells a number of engaging stories about his rise from FBI street agent -- one undercover assignment entailed parading around nude in the locker room of a local health club frequented by a prominent mobster -- to his mob-busting days as a federal prosecutor in the famed Southern District of New York. There are a few too many gratuitous bromides bestowed on colleagues and even neighbors. But these accolades serve the purpose, intended or not, of contrasting starkly with Freeh's portrait of Clinton as a man whose only moral compass is political expediency. When a judge cited Clinton in 1999 for contempt for lying in the Paula Jones case, Freeh describes it as a disgrace equal only to Richard M. Nixon's. If it had been him, Freeh writes, "I would be so devastated that I might never show my face in public again. The ex-president, however, seems to suffer no such pangs of conscience."

In retrospect, it should have been clear to both men that this was a doomed relationship. Could there be two more different people? Freeh, a former altar boy and a moralist at his core, always carried a worn prayer book in his suit jacket. But Freeh was impressed with the breadth of Clinton's questions in their first meeting, and by the time Clinton assures Freeh there will be no political interference if he takes the job, Freeh has joined the legions of the charmed. When Clinton sits down, without prompting, to write a birthday greeting to Freeh's 7-year-old son, the deal is sealed.

Freeh acknowledges making mistakes in the relationship. He lacked tact in trying to distance himself. He turned down an early dinner invitation to the White House with the Clintons and Tom Hanks; he even sent back his White House pass with a terse note, indicating he would sign in every time he came calling. "It was seemingly a declaration of open hostility on my part," he writes. But, he argues, "I was the nation's top cop," and just a few months into his tenure, Clinton was already the subject of a criminal investigation in what became known as Whitewater. "Until the matter was sorted out," Freeh writes, "I had to be accountable for every trip I made to the building where the president worked and lived."

The final stake through the relationship's heart, however, was the president's response to the June 1996 bombing of Khobar Towers, an American military facility in Saudi Arabia, in which 19 Americans were killed. It is fitting that Freeh opens My FBI with Khobar Towers; there was no case he cared more deeply about or pursued more relentlessly. It became his Moby-Dick. Only hours after the bombing, Clinton dispatched the FBI to track down the perpetrators, promising the nation they would not go unpunished. Freeh personally oversaw the case, and when it soon began to appear that top Iranian government officials might be behind the attack, Freeh says the investigation stalled: "Where I found myself most stymied [was] not halfway around the world on the Arabian Peninsula but at home, a half dozen blocks up Pennsylvania Avenue." The problem, in Freeh's view, was that in May 1997 an Iranian moderate, Mohammad Khatami, had been elected president and seemed to be the United States' best hope of normalizing relationships. "The Khobar Towers investigation was not going to get in the way of that," Freeh writes.

The tale of duplicity Freeh tells is complicated, but the basic outlines are these: The Saudis, who had suspects in custody, had communicated in a limited way their findings of Iranian involvement to the FBI and the White House. To put a legal case together, however, the bureau needed access to the suspects, and Freeh was told by Prince Bandar bin Sultan, the Saudi ambassador in Washington, that this would happen only if the president and his top aides exerted pressure on Crown Prince Abdullah, the kingdom's de facto leader. The Saudis, however, said they were receiving U.S. signals to back off, not to bull ahead with the investigation. Clinton and his aides denied this to Freeh, but in the end, Freeh came to believe the Saudis' version.

Among the most telling incidents for Freeh was a meeting that occurred in September 1998 between the crown prince and the president at the Hay Adams hotel in Washington. Freeh was assured by Clinton's national security adviser, Samuel R. "Sandy" Berger, that Clinton had pressed Abdullah for U.S. access to the Saudi-held suspects, but others present told Freeh that Clinton barely raised the subject and sympathized with the Saudis' reluctance to cooperate. Clinton, Freeh writes, then promptly asked Abdullah for a contribution to his presidential library. (I learned through my own reporting at the time that Freeh later secretly referred Clinton's library request for grand jury investigation, but he does not reveal this here, presumably because of grand jury secrecy rules.) Frustrated, Freeh then made an extraordinary out-of-chain of command pitch to former president George H.W. Bush, who also was scheduled to visit with Abdullah. Freeh called Bush, much favored in Saudi Arabia due to the 1991 Gulf War, and asked him to make the request that Clinton wasn't making. The former president agreed, and two days later, Abdullah told Freeh that the suspects would be made available. "I have no doubt that, but for President Bush's personal intervention, we would never have gotten access," Freeh writes. Six weeks later, the information from the interviews and other evidence turned over by the Saudis showed incontrovertibly that the attack had been funded, Freeh writes, by senior Iranian officials. He adds that, after he reported these findings, Berger convened a meeting in the West Wing's Situation Room to discuss them. But instead of dealing with the evidence of Iranian complicity, Freeh writes, the meeting focused on how to deal with the press and Congress should the news leak. (A "Script A" and a "Script B" had been prepared.) No other moment in his eight years matched the disappointment of that meeting: "We had the goods on them, cold, yet the Clinton administration miserably failed to seek any redress," Freeh writes. The case limped along until the new President Bush took office. Six months later, a grand jury indicted 14 defendants, mostly the active participants in the plot, and accused the Iranian government of directing the attack -- though no Iranian officials were indicted, a fact that Freeh curiously fails to explain.

Freeh devotes a scant two chapters to the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks and their aftermath, explaining that enough newsprint and news hours already have been dedicated to what went wrong without his rehashing the details. This will be too little for many; critics have blasted Freeh for pursuing his Khobar Towers obsession while his FBI missed the gathering al Qaeda plot at home. Though Freeh resigned three months before Sept. 11, the plot was assembled on his watch, as was the FBI counterterrorism apparatus that failed to thwart it. But he has a few points about Sept. 11 that he is determined to make. While acknowledging "many shortcomings" of his own, Freeh blames Congress for the much-reported antiquated state of the FBI's computer system, pointing out that the bureau begged Congress for funds that were not forthcoming. He complains that from 2000-02, the bureau asked for 1,900 new employees for its counterterrorism program and got only 76.

But the heart of Freeh's complaint is that until Sept. 11, terrorism was viewed by both the Clinton and Bush administrations as a law enforcement issue -- sifting through bomb sites looking for evidence, as the FBI did with Khobar Towers -- and not as an act of war, as he now argues that it should have been. "I don't know an agent who thought that was sufficient to the cause, or anyone who believed that a criminal investigation was a reasonable alternative to military or diplomatic action," he writes. The United States had gone after Osama bin Laden with a few Tomahawk cruise missiles in 1998 in retaliation for the bombings of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania; the CIA had made covert attempts to get bin Laden; and the State Department had harangued his Taliban patrons. But these attempts were all lame, Freeh argues, because the United States lacked the political spine to put its full force behind the efforts. Freeh points out that the FBI had helped secure indictments against bin Laden in 1998 and 1999 and, along with the CIA, missed nabbing Khalid Sheik Mohammed, the Sept. 11 plot's mastermind, in Qatar in 1996 when he was apparently tipped off by a Qatari official. In 2000, Freeh flew to Pakistan and personally appealed to President Pervez Musharraf to pressure his Taliban allies to arrest bin Laden. "If [the U.S.] government had a different mind-set, the secretaries of state and defense would have been in Lahore with me, or instead of me," Freeh writes. This negligence, he argues, emboldened the terrorists. "The image of a lumbering giant stumbling around with a sign on its back reading 'Kick Me' was not lost on our enemies," he notes.

My FBI is ultimately a sad tale, and it's clear Freeh saw it this way, too. He had planned to resign before the end of Clinton's term but held off until the president left office because he worried that Clinton might replace him with someone who would damage the FBI. "Not only was he actively hostile toward me, he was hostile to the FBI generally," Freeh writes. "My departure might be one last opportunity for retaliation."

Reviewed by Elsa Walsh

From AudioFile

The memoir of the former director of the FBI covers not only the political scandals of the '90s, but also the Waco tragedy, the Oklahoma bombing, and efforts to eliminate the American Mafia. Adam Grupper narrates Freeh's take on crime-busting and political hanky-panky with crisp intelligence. Freeh's anecdotes, however, are strongly slanted against the decisions made by President Clinton, particularly regarding the bombing of the Khobar Towers in 1996. Freeh praises the actions of the first President Bush, who used his friendship with Saudi Prince Abdullah to gain Freeh access to bombing suspects, but paints Clinton as a savvy politician whose moral compass points only to expediency. Grupper reads even the most biased claims with appropriate journalistic objectivity. S.J.H.

About Author

LOUIS J. FREEH served as director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation from 1993 to 2001. He now is senior vice chairman of MBNA.

Book Dimension :

length: (cm)23.5 width:(cm)15.6

作者简介

目录信息

读后感

我一直认为和当下我们中的某些人相比,美国人整体是善良的。飞机上一直在读本书,感觉FREEH在做事,有担当,很男人(现在流行说“纯爷们儿”)。每个人一天都有24,权力层面的人,站得越高应该作用越大,在每一个24对国家社会做出的的贡献也越大。我们这里一定有人一天不是24,...

评分我一直认为和当下我们中的某些人相比,美国人整体是善良的。飞机上一直在读本书,感觉FREEH在做事,有担当,很男人(现在流行说“纯爷们儿”)。每个人一天都有24,权力层面的人,站得越高应该作用越大,在每一个24对国家社会做出的的贡献也越大。我们这里一定有人一天不是24,...

评分我一直认为和当下我们中的某些人相比,美国人整体是善良的。飞机上一直在读本书,感觉FREEH在做事,有担当,很男人(现在流行说“纯爷们儿”)。每个人一天都有24,权力层面的人,站得越高应该作用越大,在每一个24对国家社会做出的的贡献也越大。我们这里一定有人一天不是24,...

评分我一直认为和当下我们中的某些人相比,美国人整体是善良的。飞机上一直在读本书,感觉FREEH在做事,有担当,很男人(现在流行说“纯爷们儿”)。每个人一天都有24,权力层面的人,站得越高应该作用越大,在每一个24对国家社会做出的的贡献也越大。我们这里一定有人一天不是24,...

评分我一直认为和当下我们中的某些人相比,美国人整体是善良的。飞机上一直在读本书,感觉FREEH在做事,有担当,很男人(现在流行说“纯爷们儿”)。每个人一天都有24,权力层面的人,站得越高应该作用越大,在每一个24对国家社会做出的的贡献也越大。我们这里一定有人一天不是24,...

用户评价

**书籍评价二:** 这本书的叙事结构着实令人赞叹,它没有采用传统的线性叙事,而是巧妙地在过去、现在与未来之间进行跳跃,这种非线性的叙事方式非但没有造成阅读上的混乱,反而极大地增强了悬念和故事的层次感。我尤其欣赏作者对环境和氛围的营造能力,那些关于荒凉之地或繁华都市的细致描写,仿佛自带声效和气味,让我仿佛能闻到文字中散发出的尘土味或香水味。故事的主角们,他们的内心挣扎与道德困境,被揭示得极为坦诚和残酷。他们不是完美的英雄,而是充满了人性的弱点和矛盾的个体,这使得他们的选择和命运更具共鸣感和现实的重量。在阅读高潮部分时,我甚至能感受到心跳的加速,作者对紧张局势的把控简直是教科书级别的。这本书成功地在娱乐性和艺术性之间找到了一个极佳的平衡点,它既能满足我对精彩故事的渴望,又能提供深层次的哲学思考。

评分**书籍评价一:** 读完这本厚重的历史画卷,我简直被深深地震撼了。作者以极其细腻的笔触,将那个风云变幻的年代刻画得入木三分。书中的人物群像栩栩如生,无论是庙堂之上的权谋角力,还是市井之间的酸甜苦辣,都被描摹得淋漓尽致。特别是对于某个关键历史事件的深入剖析,简直可以说是石破天惊,它颠覆了我过去多年来的固有认知。阅读过程中,我时常需要停下来,消化那些复杂的人物关系和错综的事件脉络。那种沉浸式的体验,仿佛我本人就置身于历史的洪流之中,亲眼见证着那些重大决策的酝酿与执行。文字的张力十足,节奏感把握得恰到好处,高潮迭起,让人完全无法将书本放下。尽管篇幅不菲,但每一个章节都充满了信息量和思想的深度,读完后感觉自己的历史观得到了极大的拓展和重塑。这本书绝对不是那种快餐式的消遣读物,它更像是一场思想的深度洗礼,值得反复咀嚼和深思。

评分**书籍评价五:** 这本书最吸引我的地方,在于它对人性阴暗面近乎残忍的描摹,但这种描摹并非单纯的猎奇或煽情,而是建立在对人类心理机制深刻洞察的基础之上。作者似乎拥有洞悉人心最深处恐惧和欲望的能力,将角色在极端压力下的反应刻画得真实到令人心悸。我感觉自己像是一个旁观者,被迫直视人类文明光环下那些丑陋的、原始的冲动。故事的情感张力非常饱和,它探讨了爱、背叛、救赎与沉沦这些永恒的主题,但处理的角度非常新颖,总能从一个意想不到的侧面切入。这种阅读体验是沉重而深刻的,它带来的震撼不是一时的刺激,而是会长时间地留存在脑海中,让你反复审视自己与他人的关系。读完之后,我需要很长时间才能从那种压抑但又极具穿透力的氛围中抽离出来,可见其感染力的强大。

评分**书籍评价三:** 这是一本在文学性上达到了极高水准的作品。作者的遣词造句充满了古典韵味与现代张力的奇妙结合,很多句子本身就是可以摘录下来的艺术品。我发现自己时不时会停下来,反复品味那些精妙的比喻和排比,它们不仅服务于情节推进,更提升了作品的整体美学价值。情节的推进并非一蹴而就,而是像慢火炖煮的浓汤,需要耐心去品尝才能体会到其中蕴含的复杂滋味。书中对某些社会现象的讽刺入木三分,那种不动声色的批判,比直白的控诉更有力量,它迫使读者主动去思考隐藏在文字背后的社会结构问题。整本书读下来,我感觉自己经历了一场漫长而充实的精神远征,它拓展了我对“美”和“真实”的理解边界。对于追求纯粹文学享受的读者来说,这本书绝对不容错过,它真正体现了文字的魔力。

评分**书籍评价四:** 坦白说,这本书的开篇有些晦涩,需要投入额外的精力去适应作者设定的独特世界观和那些拗口的专有名词。但是,一旦跨过了最初的“入门门槛”,后续的阅读体验简直是令人震撼的渐入佳境。作者构建的这个世界观宏大且逻辑自洽,每一个设定背后似乎都有着深厚的理论支撑,让人由衷地佩服其构建世界的想象力与严谨性。角色之间的对话充满了智慧的火花,很少有无意义的寒暄,每一次交流都推动着剧情发展或揭示了人物的隐藏动机。更让我印象深刻的是,这本书巧妙地运用了悬疑元素,尽管我自诩是推理高手,但几次关键的谜团揭晓都完全出乎我的意料,作者的布局之深远,简直让人拍案叫绝。它提供了一种智力上的挑战,同时又给予了巨大的满足感,是那种读完后会立刻想找人讨论细节的佳作。

评分Finally Done! Louie对PRC意见挺大,不过他用律师腔念叨了这好几百页还是很有料的。只给四颗星星是因为过剩的美式法治至上精神,还有最后过长的致谢名单。。。

评分Finally Done! Louie对PRC意见挺大,不过他用律师腔念叨了这好几百页还是很有料的。只给四颗星星是因为过剩的美式法治至上精神,还有最后过长的致谢名单。。。

评分Finally Done! Louie对PRC意见挺大,不过他用律师腔念叨了这好几百页还是很有料的。只给四颗星星是因为过剩的美式法治至上精神,还有最后过长的致谢名单。。。

评分Finally Done! Louie对PRC意见挺大,不过他用律师腔念叨了这好几百页还是很有料的。只给四颗星星是因为过剩的美式法治至上精神,还有最后过长的致谢名单。。。

评分Finally Done! Louie对PRC意见挺大,不过他用律师腔念叨了这好几百页还是很有料的。只给四颗星星是因为过剩的美式法治至上精神,还有最后过长的致谢名单。。。

相关图书

本站所有内容均为互联网搜索引擎提供的公开搜索信息,本站不存储任何数据与内容,任何内容与数据均与本站无关,如有需要请联系相关搜索引擎包括但不限于百度,google,bing,sogou 等

© 2026 book.quotespace.org All Rights Reserved. 小美书屋 版权所有