具体描述

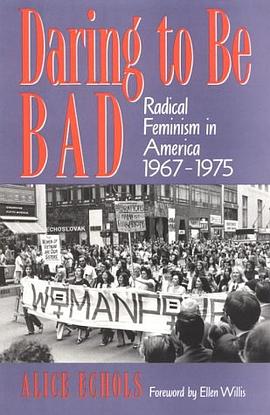

Author Alice Echols wrote in the introduction to this 1989 book, “It has been over twenty years since the emergence of the women’s liberation movement and yet, with the exception of Sara Evans’s ground-breaking monograph Personal Politics: The Roots of Women's Liberation in the Civil Rights Movement & the New Left, there has been no book-length scholarly study of the movement… It is my hope that this study will begin to fill the lacuna in the literature. This book analyzes the trajectory of the radical feminist movement from its beleaguered beginnings in 1967, through its ascendancy as the dominant tendency within the movement, to its decline and supplanting by cultural feminism in the mid-‘70s. This is not a comprehensive history of the contemporary women’s movement… Rather, this is a thorough history of one wing of the women’s movement.” (Pg. 5-6)

Later, she adds, “My task is to make the ‘60s, or at least the women’s rebellion of that era, more comprehensible. It is also my hope that by excavating the history of radical feminism I can demonstrate that radical feminism was fare more varied and fluid, not to mention more radical, than what is generally thought of as radical feminism today… it is my hope that by illuminating the reasons for the movement’s decline, this study will help to stimulate discussion on how the movement might be revitalized.” (Pg. 19)

She defines ‘radical feminists’ as those “who opposed the subordination of women’s liberation to the left and for whom male supremacy was not a mere epiphenomenon of capitalism… Radical feminism rejected both the politico position that socialist revolution would bring about women’s liberation and the liberal feminist solution of integrating women into the public sphere. Radical feminists argued that women constituted a sex-class, that relations between women and men needed to be recast in political terms, and that gender rather than class was the primary contradiction… And in defying the cultural injunction against female self-assertion and subjectivity, radical feminists ‘dared to be bad.’” (Pg. 3-4)

She laments, “by the early ‘70s radical feminism began to flounder, and after 1975 it was eclipsed by cultural feminists… With the rise of cultural feminism the movement turned its attention away from opposing male supremacy to creating a female counterculture… where ‘male’ values would be exorcised and ‘female’ values nurtured… And by 1975 radical feminism virtually ceased to exist as a movement… activism became largely the province of liberal feminists.” (Pg. 4-5)

She notes, ‘Radical women agreed that they needed to organize separately from men, but they disagreed over the nature and purpose of the separation. Indeed, was it a separation or a divorce that they wanted? … Should women’s groups focus exclusively on women’s issues, or should they commit themselves to struggling against the war and racism as well?... And, perhaps most troublesome of all, what or who was the enemy? From the beginning radical women debated these questions, often hotly.” (Pg. 51)

She acknowledges, “it is fair to say that most early women’s liberationists were college-educated women in their mid-to-late twenties who grew up in middle class families… most of these women were unable to parlay their college degrees into good-paying jobs.” (Pg. 65) She adds, “These groups were composed of women whose backgrounds were very similar and who were denizens of a Movement subculture which was in some respects as exclusionary as a sorority… the cliquishness of these groups impeded the acculturation of new women outside the left and promoted parochialism within the movement.” (Pg. 72)

Of the famous 1968 protest at the Miss America pageant, she points out, “Some women… tossed ‘instruments of torture to women’---high-heeled shoes, bras, girdles… into a ‘Freedom Trash Can’ … Although the protesters had hoped to turn the contents of the ‘Freedom Trash Can,’ they were prohibited from doing so by the city… The women decided to comply with the city order because they envisioned the protest as a ‘zap action’ to raise the public’s consciousness about beauty contests rather than as an opportunity to do battle with the police… The protesters were also anxious to avoid arrests because the group lacked the resources to cover legal expenses… But at least one of the organizers of the protest leaked word of the bra-burning to the press to stimulate media interest in the action. Those feminists who sanctimoniously disavowed bra-burning as a media fabrication were wither misinformed or disingenuous.” (Pg. 93-94)

She observes, “From the beginning, the women’s liberation movement was internally fractured. In fact, it is virtually impossible to understand radical feminism without referring to the movement’s divided beginnings. Radical feminism was, in part, a response to the anti-feminism of the left and the reluctant feminism of the politicos. Radical feminists’ tendency to privilege gender over race and class, and to treat women as a homogenized unity, was in large measure a reaction to the left’s dismissal of gender as a ‘secondary contradiction.’ Moreover, the politico-feminist schism was so debilitating that is seemed to confirm radical feminists’ suspicions that difference and sisterhood were mutually exclusive.” (Pg. 101)

She points out, “black women who identified with black power were typically unsympathetic to women’s liberation. Even black women who spoke out against sexism felt that racism was by far the more pressing issue. Ironically, the rise of black power, so important in fostering feminist consciousness among white women, had very different consequences for black women. Black power, as it was articulated by black men, involved laying claim to masculine privileges denied them by white supremacist society. Within the black liberation movement black women were expected to ‘step back into a domestic, submissive role’ so that black men could freely exercise their masculine prerogatives.” (Pg. 106)

Of one group, she notes, “‘The Feminists’ were the first of many radical feminist groups to interpret ‘the personal is political’ prescriptively. For ‘The Feminists,’ one’s personal life was a reflection of one’s politics, a barometer of one’s radicalism and commitment to feminism. While ‘The Feminists’ proscribed heterosexual relationships rather than heterosexual sex, it was just a matter of time before the standard became even narrower and more confining. Indeed, ‘The Feminists’ advocacy of separatism established the theoretical foundation for lesbian separatism.” (Pg. 185)

Of the ending of the New York Radical Feminists group [aka “Stanton-Anthony”], she recounts, “The dissolution of Stanton-Anthony marked the end of [Shulamith] Firestone’s and [Anne] Koedt’s involvement with the organized movement. Reportedly they felt they had been deposed because their analysis was too radical. By the time Firestone’s book ] was published in October 1970, she had already dropped out of the movement. Koedt co-edited ‘Notes from the Third Year’ and the aboveground anthology Radical Feminism, which was published in 1973, but she kept her distance from the movement… [Susan] Brownmiller’s analysis suggests that Koedt and Firestone sought personal control. But it seems just as likely that they wanted the power to define the movement and prevent its attenuation. However, by 1970, this was a power the founders were rapidly losing.” (Pg. 195)

She continues, “by 1973, the radical feminist movement was actually in decline. The groups responsible for making the important theoretical breakthroughs were either dead or moribund… A number of movement pioneers had withdrawn from the movement, often… as a result of being attacked as ‘elitist,’ ‘middle class,’ or ‘unsisterly.’ … Then there were the divisive struggles over class, elitism, and sexual preference which started to consume the movement in 1970… The radical feminist wing of the movement became so absorbed in its own internal struggles that it sometimes found it difficult to look outside itself, to focus on the larger problem of male supremacy.” (Pg. 198)

Of another important radical group, she comments, “Estranged from the larger feminist community, The Furies grew increasingly isolated an insular. In March 1972, the group challenged [founder Rita Mae] Brown on her imperious style. Brown considered it a purge, while others claim Brown left before she could be expelled. [Charlotte] Bunch contends that Brown’s departure set in motion a ‘dynamic of backbiting and internal fighting,’ which Bunch felt would continue unabated unless the group disbanded. The Furies dissolved in April 1972, a month after Brown’s departure and only a year after its founding… it is ironic that The Furies, who did so much to advance the movement’s understanding of women’s differences, were completely unable to tolerate differences among themselves.” (Pg. 238)

She states, “[The Redstockings] insinuated that Ms. magazine was part of a CIA strategy to replace radical feminism with liberal feminism. Ms. magazine had been a source of irritation to many feminists since its inception. A number of feminist writers were especially angry when Ms. first formed and went outside the movement for its writers and editors… Generally, radical feminists complained of the magazine’s liberal orientation and attributed Ms.’s denatured feminism to the magazine’s commercial orientation.” (Pg. 266)

She concludes, “By 1975 it was too late for a revival of radical feminism. The economic, political, and cultural constriction of the ‘70s and the collapse of other oppositional movements in this period made radical activism of any sort difficult. Much of the movement’s original leadership had been ‘decapitated’ during the acrimonious struggles over class and elitism. And, of course, a number of the founders had retreated from the movement when lesbianism was advocated as the natural and logical consequence of feminism… radical feminism was derailed, at least in part, by its own theoretical limitations… NOW was a major beneficiary of radical feminism’s disintegration as first the schisms and later the countercultural focus encouraged some radical feminists to join an organization which they had initially disparaged… But liberal feminism had floundered without the benefit of a vocal radical feminist movement… That the radical feminist movement was unable to sustain itself is hardly remarkable. This is, after all, the fate of all social change movements.” (Pg. 284-285)

This is a highly informative, very detailed summary of a crucial period in the development of the modern women’s movement; and Echols doesn’t shy away from discussing frankly the “problems” the movement had (“Third Wavers,” take note!). This book will be “must reading” for anyone studying the early “radical” days of the women’s movement.

作者简介

Alice Echols is Professor of History and the Barbra Streisand Chair of Contemporary Gender Studies at the University of Southern California. She has written four books that explore the culture and politics of the “long Sixties,” including Scars of Sweet Paradise: The Life and Times of Janis Joplin and Hot Stuff: Disco and the Remaking of American Culture. Her forthcoming book explores an earlier period of U.S. history. Shortfall: Family Secrets, Financial Collapse, and a Hidden History of American Banking (The New Press), concerns a devastating Depression-era banking scandal and its connection to the cratering of the country’s building and loan industry. At the center of her narrative is her maternal grandfather, an ambitious building and loan operator in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Shortfall chronicles the fall-out from the industry's failure, examines how its history came to be forgotten, and the consequences that followed from that cultural forgetting. It stands as a cautionary tale about the seductions and dangers of unfettered capitalism. She lives in Los Angeles.

目录信息

读后感

评分

评分

评分

评分

用户评价

这本书的书名就充满了一种挑战性,而内容更是将这种挑战性发挥到了极致。作者以一种极其大胆和不加修饰的笔触,深入探讨了那些被社会普遍视为禁忌和负面的主题。我非常欣赏作者在处理这些敏感话题时的勇气,她没有回避,而是直面它们,并通过生动的人物塑造和扣人心弦的情节,让读者不得不去思考这些问题。书中的人物,都不是脸谱化的英雄或恶棍,他们是复杂的个体,有着各自的动机和挣扎。我尤其被书中某些角色的选择所震撼,那些看似“错误”的决定,却在作者的笔下,充满了合理性和人性的逻辑。这让我开始反思,我们所定义的“正确”,是否真的那么绝对?这本书让我看到了人性中那些不那么光彩的一面,但同时,也让我看到了在这些阴影中,依然闪烁着微弱却坚韧的光芒。它不是一本轻松的书,它会让你感到不安,让你质疑,让你思考。但正是这种不安和质疑,才促使我们去成长,去进步。我可以说,这本书彻底颠覆了我对许多事物的看法,它就像一把钥匙,打开了我认知世界的新大门。

评分这本书的吸引力,不仅仅在于它引人入胜的情节,更在于它对人性的深刻洞察。作者似乎能够穿透表象,直抵人心的最隐秘之处,并将那些复杂、矛盾甚至令人不安的情感,用极其细腻和真实的笔触描绘出来。我常常在阅读时,被书中某些角色的选择所震撼,那些看似“错误”的决定,却在作者的笔下,充满了令人信服的动机和逻辑。这种对人性的真实刻画,让我感到一种前所未有的震撼。它让我意识到,我们所看到的“好”与“坏”,往往只是一个表象,其背后隐藏着更为复杂的驱动力。这本书的叙事节奏把握得非常好,既有紧张刺激的冲突,也有细腻温情的描绘,让我始终保持着高度的阅读兴趣。作者的文字功底也毋庸置疑,她能够用最简洁的语言,传达出最深刻的含义,让我反复品味,回味无穷。它不仅仅是一个故事,更像是一次对自我边界的探索,一次对社会规则的审视。它鼓励我去质疑,去挑战,去勇敢地面对那些不那么“完美”的自己。

评分从装帧设计到文字内容,这本书都散发着一种与众不同的气质。它不是那种浮于表面的励志读物,也不是那种满足于讲述一个简单故事的平庸之作。相反,它像一个深邃的漩涡,将我卷入其中,让我无法自拔。作者的语言风格极其独特,既有诗意的描绘,又不乏犀利的洞察,仿佛能直接触及到读者的灵魂深处。书中对人物内心世界的探索,更是达到了令人发指的深度。那些隐藏在潜意识里的欲望,那些被压抑的情感,都被作者一一挖掘出来,并用最真实、最赤裸的方式呈现。我常常在阅读时,感到一种强烈的共鸣,仿佛作者写的就是我内心的某些声音。书中的情节发展,也绝非按部就班,而是充满了出人意料的转折,每一次的转折都让我对故事有了更深的理解,也让我对人性的复杂有了更深的体会。它让我看到,原来“坏”也可以是一种选择,一种反抗,一种追求极致自由的途径。这种视角,无疑是极具颠覆性的,它挑战了我一直以来所秉持的道德观念,让我开始重新审视那些被社会奉为圭臬的原则。

评分读完这本书,我仿佛经历了一场荡涤心灵的旅程。作者的文字就像一把锋利的解剖刀,精准地剖析了人性的复杂与矛盾,那些潜藏在文明表象下的原始冲动,被她毫无保留地展现出来。书中的每一个场景,每一个对话,都充满了象征意义,每一次阅读,都能挖掘出新的层次和解读。我尤其惊叹于作者在描绘人物内心挣扎时的精准度,那些微小的心理变化,那些不易察觉的情感波动,都被她捕捉得如此到位。阅读的过程,就像是在和书中人物一同经历一场内心的风暴,感受他们的痛苦,分享他们的喜悦,最终见证他们的成长。这本书并非适合所有读者,它需要你有一颗愿意去探索、去冒险的心,愿意去触碰那些敏感的、甚至有些令人不安的主题。但如果你做好了准备,那么这本书一定会给你带来意想不到的收获。它挑战了我对“好”与“坏”的简单定义,让我开始思考,在某些极端情况下,坚持“正确”的代价是什么?而所谓的“坏”,又是否包含着某种不可或缺的真实性?作者并没有给出明确的答案,而是留给了读者广阔的思考空间,这正是这本书的魅力所在。它不是一本读完就可以丢弃的书,而是会留在你的记忆深处,时常被你回味和反思。

评分这本书的封面就透露着一种大胆与不羁,而内容更是将这种气质发挥到了极致。作者的叙事风格极其鲜明,她不回避人性中的阴暗面,反而将其深入挖掘,并通过生动的人物形象和扣人心弦的情节,引发读者强烈的共鸣。我尤其惊叹于作者在处理复杂人性时的坦诚,没有刻意去美化或丑化,而是展现了人性的多面性,那些光明与阴影并存的时刻,反而让角色更加真实可信。书中的情节发展,也绝非是线性叙事,而是充满了意想不到的转折,每一次的转折都让我对故事有了更深的理解,也让我对人性的复杂有了更深的体会。它让我看到,原来“坏”也可以是一种选择,一种反抗,一种追求极致自由的途径。这种视角,无疑是极具颠覆性的,它挑战了我一直以来所秉持的道德观念,让我开始重新审视那些被社会奉为圭臬的原则。读完这本书,我的脑海中会充斥着各种各样的思考,它不仅仅是一个故事,更像是一次对自我边界的探索,一次对社会规则的审视。

评分这是一本让我爱不释手的书,它的文字中蕴含着一种难以言喻的力量,能够轻易地将我带入故事的氛围之中。作者对人物心理的刻画尤为细腻,她能够捕捉到那些最微小的、最隐秘的情感波动,并将其描绘得入木三分。我常常在阅读时,感到一种强烈的共鸣,仿佛作者写的就是我内心的某些声音,或者是我曾经有过但未能表达的感受。书中的情节设计也非常巧妙,充满了出人意料的转折,每一次的转折都让我对故事有了更深的理解,也让我对人性的复杂有了更深的体会。它让我看到,原来“坏”也可以是一种选择,一种反抗,一种追求真实与自由的途径。这种视角,无疑是令人耳目一新的,它打破了我以往对很多事物的固有认知,让我开始用更加多元化的眼光去审视这个世界。它不是一本轻松的书,它会让你感到不安,让你质疑,让你思考。但正是这种不安和质疑,才促使我们去成长,去进步。

评分刚拿到这本书,就被它独特而富有冲击力的封面设计所吸引。翻开书页,作者的文字风格便立刻抓住了我的注意力。它不像那些精致雕琢的文字,反而带有一种原始的、野性的生命力,能够轻易地触动人心最深处的某些地方。我尤其欣赏作者在描绘人物内心世界时的深度,那些隐藏在潜意识中的冲动,那些被压抑的情感,都被她精准地捕捉并呈现出来。阅读的过程,就像是在和书中人物一同经历一场内心的风暴,感受他们的痛苦,分享他们的喜悦,最终见证他们的成长。这本书让我开始重新审视“好”与“坏”的定义。它让我看到,有时候,所谓的“坏”,并非全然的邪恶,它可能是一种反抗,一种对规则的挑战,一种追求真实与自由的勇气。这种视角,无疑是令人耳目一新的,它打破了我以往对很多事物的固有认知,让我开始用更加多元化的眼光去审视这个世界。它不是一本轻松的书,它会让你感到不安,让你质疑,让你思考。但正是这种不安和质疑,才促使我们去成长,去进步。

评分初读这本书,我便被其独特的风格所吸引。作者的文字充满了力量,却又不失细腻,仿佛能够直接触及读者的灵魂。书中的人物塑造极其成功,他们不再是扁平的符号,而是有血有肉、有情感、有欲望的个体。我尤其欣赏作者在描绘人物内心挣扎时的深度,那些隐藏在潜意识中的冲动,那些被压抑的情感,都被她精准地捕捉并呈现出来。阅读的过程,就像是在和书中人物一同经历一场内心的风暴,感受他们的痛苦,分享他们的喜悦,最终见证他们的成长。这本书让我开始重新审视“好”与“坏”的定义。它让我看到,有时候,所谓的“坏”,并非全然的邪恶,它可能是一种反抗,一种对规则的挑战,一种追求真实与自由的勇气。这种视角,无疑是令人耳目一新的,它打破了我以往对很多事物的固有认知,让我开始用更加多元化的眼光去审视这个世界。它不是一本轻松的书,它会让你感到不安,让你质疑,让你思考。但正是这种不安和质疑,才促使我们去成长,去进步。

评分这本书的封面设计就足够吸引我,深邃的蓝与炽烈的红交织,仿佛预示着一场关于边界、禁忌与挑战的旅程。迫不及待地翻开,首先映入眼帘的是作者独特的叙事风格,它不像那些精心雕琢、一丝不苟的文字,反而带着一种随性而又充满力量的笔触。阅读过程中,我常常被那些意想不到的转折所吸引,仿佛置身于一个精心设计的迷宫,每一步都充满了未知,却又导向更深层次的思考。作者对于人物内心的描绘尤为细腻,那些纠结、挣扎、甚至是微小的犹豫,都被刻画得入木三分。读着读着,我仿佛能听到角色的心跳,感受到他们情绪的潮起潮落。这种沉浸感是很多作品难以企及的。书中对于一些社会现象的探讨也相当深刻,它不是简单地罗列事实,而是通过人物的经历,将这些问题渗透到读者的意识深处,引发共鸣和反思。我尤其喜欢作者在处理复杂人性时的坦诚,没有刻意去美化或丑化,而是展现了人性的多面性,那些光明与阴影并存的时刻,反而让角色更加真实可信。每次合上书页,脑海中都会回荡着书中某些场景或对话,它们像种子一样在我心中发芽,让我对周围的世界有了新的认识。这本书不仅仅是一个故事,更像是一次心灵的探索,一次对自身边界的审视。它鼓励我去挑战那些固有的观念,去质疑那些理所当然的规则,去勇敢地面对内心深处那些不那么“完美”的部分。

评分从我接触到这本书的第一眼起,就被它那种扑面而来的“野性”所吸引。它不是那种循规蹈矩、按部就班的故事,而是充满了张力与不确定性。作者似乎拥有一种能够洞察人性的超能力,将那些隐藏在表面之下的暗流汹涌,描绘得淋漓尽致。书中的人物,没有一个是完美的,他们都有着各自的缺点和阴暗面,也正是因为这份真实,我才觉得他们如此鲜活,如此 relatable。尤其是主角,她的选择,她的挣扎,她的每一次突破,都像是一场与自我搏斗的战役,每一次胜利都来之不易。我常常在阅读时,不自觉地将自己的生活代入进去,思考在同样的情境下,我会如何应对?作者的文字具有一种魔力,它能轻易地将我带入故事的氛围中,让我忘记时间的流逝,忘记周遭的一切。那种被故事情节深深吸引,以至于忽略了现实世界的体验,是阅读的最高享受之一。这本书带给我的,不仅仅是阅读的乐趣,更是一种精神上的启迪。它让我意识到,所谓的“坏”,或许并非全然的负面,它也可能是一种反抗,一种对规则的挑战,一种追求自由与真实的勇气。这种视角,无疑是令人耳目一新的,它打破了我以往对很多事物的固有认知,让我开始用更加多元化的眼光去审视这个世界。

评分史料丰富,一次性能了解不少关于60年代radical feminism的细节,虽然historiography值得推敲。而且Echols与Willis应该都有些怀念activism。

评分The Eruption of Difference. 1). 以justice为核心的社运如何对待自己内部的领导权问题和权力关系呢?本文讲述了六七十年代美国女权运动内部的phobia about leaders and elitism, 介绍了the Class Workshop的反精英反偶像agenda,他们抨击被媒体放大的女权明星,但媒体还是继续指认个别人作为运动的领袖和发言人,把领导的认定权从运动身上剥夺,这种反精英主义本身也打击了有才能的参与者的积极性;2). 女性主义和性解放 与女同主义的关系应如何?在一众倡导者的推动下,运动从恐同走向有争议的理解和接纳

评分The Eruption of Difference. 1). 以justice为核心的社运如何对待自己内部的领导权问题和权力关系呢?本文讲述了六七十年代美国女权运动内部的phobia about leaders and elitism, 介绍了the Class Workshop的反精英反偶像agenda,他们抨击被媒体放大的女权明星,但媒体还是继续指认个别人作为运动的领袖和发言人,把领导的认定权从运动身上剥夺,这种反精英主义本身也打击了有才能的参与者的积极性;2). 女性主义和性解放 与女同主义的关系应如何?在一众倡导者的推动下,运动从恐同走向有争议的理解和接纳

评分The Eruption of Difference. 1). 以justice为核心的社运如何对待自己内部的领导权问题和权力关系呢?本文讲述了六七十年代美国女权运动内部的phobia about leaders and elitism, 介绍了the Class Workshop的反精英反偶像agenda,他们抨击被媒体放大的女权明星,但媒体还是继续指认个别人作为运动的领袖和发言人,把领导的认定权从运动身上剥夺,这种反精英主义本身也打击了有才能的参与者的积极性;2). 女性主义和性解放 与女同主义的关系应如何?在一众倡导者的推动下,运动从恐同走向有争议的理解和接纳

评分史料丰富,一次性能了解不少关于60年代radical feminism的细节,虽然historiography值得推敲。而且Echols与Willis应该都有些怀念activism。

相关图书

本站所有内容均为互联网搜索引擎提供的公开搜索信息,本站不存储任何数据与内容,任何内容与数据均与本站无关,如有需要请联系相关搜索引擎包括但不限于百度,google,bing,sogou 等

© 2026 book.quotespace.org All Rights Reserved. 小美书屋 版权所有