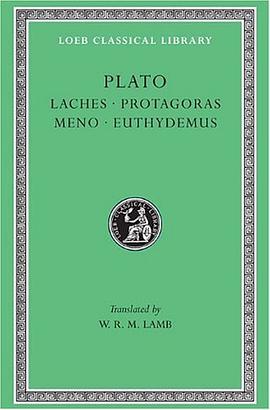

Laches. Protagoras. Meno. Euthydemus pdf epub mobi txt 电子书 下载 2026

- 柏拉图

- 薇依

- 哲学

- SJC

- Platon

- Plato

- English

- 古希腊语

- Plato

- Dialogues

- Socratic

- Philosophy

- Ethics

- Knowledge

- Reason

- Dialogue

- Argument

- Logic

具体描述

Plato, the great philosopher of Athens, was born in 427 BCE. In early manhood an admirer of Socrates, he later founded the famous school of philosophy in the grove Academus. Much else recorded of his life is uncertain; that he left Athens for a time after Socrates' execution is probable; that later he went to Cyrene, Egypt, and Sicily is possible; that he was wealthy is likely; that he was critical of 'advanced' democracy is obvious. He lived to be 80 years old. Linguistic tests including those of computer science still try to establish the order of his extant philosophical dialogues, written in splendid prose and revealing Socrates' mind fused with Plato's thought.

In Laches, Charmides, and Lysis, Socrates and others discuss separate ethical conceptions. Protagoras, Ion, and Meno discuss whether righteousness can be taught. In Gorgias, Socrates is estranged from his city's thought, and his fate is impending. The Apology (not a dialogue), Crito, Euthyphro, and the unforgettable Phaedo relate the trial and death of Socrates and propound the immortality of the soul. In the famous Symposium and Phaedrus, written when Socrates was still alive, we find the origin and meaning of love. Cratylus discusses the nature of language. The great masterpiece in ten books, the Republic, concerns righteousness (and involves education, equality of the sexes, the structure of society, and abolition of slavery). Of the six so-called dialectical dialogues Euthydemus deals with philosophy; metaphysical Parmenides is about general concepts and absolute being; Theaetetus reasons about the theory of knowledge. Of its sequels, Sophist deals with not-being; Politicus with good and bad statesmanship and governments; Philebus with what is good. The Timaeus seeks the origin of the visible universe out of abstract geometrical elements. The unfinished Critias treats of lost Atlantis. Unfinished also is Plato's last work of the twelve books of Laws (Socrates is absent from it), a critical discussion of principles of law which Plato thought the Greeks might accept.

The Loeb Classical Library edition of Plato is in twelve volumes.

作者简介

Plato, the great philosopher of Athens, was born in 427 BCE. In early manhood an admirer of Socrates, he later founded the famous school of philosophy in the grove Academus. Much else recorded of his life is uncertain; that he left Athens for a time after Socrates’ execution is probable; that later he went to Cyrene, Egypt, and Sicily is possible; that he was wealthy is likely; that he was critical of ’advanced’ democracy is obvious. He lived to be 80 years old. Linguistic tests including those of computer science still try to establish the order of his extant philosophical dialogues, written in splendid prose and revealing Socrates’ mind fused with Plato’s thought.

In Laches, Charmides, and Lysis, Socrates and others discuss separate ethical conceptions. Protagoras, Ion, and Meno discuss whether righteousness can be taught. In Gorgias, Socrates is estranged from his city’s thought, and his fate is impending. The Apology (not a dialogue), Crito, Euthyphro, and the unforgettable Phaedo relate the trial and death of Socrates and propound the immortality of the soul. In the famous Symposium and Phaedrus, written when Socrates was still alive, we find the origin and meaning of love. Cratylus discusses the nature of language. The great masterpiece in ten books, the Republic, concerns righteousness (and involves education, equality of the sexes, the structure of society, and abolition of slavery). Of the six so-called dialectical dialogues Euthydemus deals with philosophy; metaphysical Parmenides is about general concepts and absolute being; Theaetetus reasons about the theory of knowledge. Of its sequels, Sophist deals with not-being; Politicus with good and bad statesmanship and governments; Philebus with what is good. The Timaeus seeks the origin of the visible universe out of abstract geometrical elements. The unfinished Critias treats of lost Atlantis. Unfinished also is Plato’s last work of the twelve books of Laws (Socrates is absent from it), a critical discussion of principles of law which Plato thought the Greeks might accept.

目录信息

General Introduction

List Of Plato’s Works

Laches

Protagoras

Meno

Euthydemus

Index

· · · · · · (收起)

读后感

评分

评分

评分

评分

用户评价

从文学欣赏的角度来看,这本书的叙事手法简直是一绝。它不是那种枯燥的说教,而是通过一系列生动的对话场景来展开哲学的探讨。我特别喜欢那些场景的描绘,虽然简略,但极具画面感。想象一下,在一个午后的雅典,阳光斜射在人物的衣袍上,苏格拉底带着他标志性的面容,开始了他的‘拷问’。这种代入感,让原本抽象的哲学概念变得鲜活可感。它不像教科书那样冷冰冰地陈述定义,而是将‘真理’的追寻过程本身,变成了一场充满张力的戏剧。比如,当一个自认为无所不知的智者被苏格拉底几句话绕得哑口无言时,那种智识上的挫败感,通过文字被清晰地传达出来,让人拍案叫绝。这种将辩证法融入到文学叙事中的技巧,可以说是古希腊思想留给后世最宝贵的遗产之一。

评分说实话,这本书对现代人的影响,远超乎我的预期。我原本以为,这些古代的思辨对于我们处理当下的信息爆炸和道德困境,帮助有限。但事实是,它提供了一种‘慢思考’的范式。我们现在习惯于快速形成观点并发表意见,但这本书里强调的,是‘未经审视的生活不值得过’。它让你停下来,去追溯每一个概念的源头,去质疑那些你从未质疑过的“常识”。我发现,当我试图用书中那种严格的定义和推导逻辑去审视我日常工作中的某些决策时,许多原本看似理所当然的流程,立刻就暴露出了其逻辑上的薄弱点。这种结构性的反思能力,是这本书给予我的最宝贵的‘工具’,它教会我的不是‘应该相信什么’,而是‘应该如何思考’。

评分这本书的魅力,某种程度上,在于它对“知识”和“能力”之间界限的反复模糊和探讨。我读到关于某些技能掌握的对话时,会忍不住联想到我们现在社会对“专业性”的崇拜。但苏格拉底似乎总是在暗示,真正的洞察力,往往超越了具体的专业领域。他挑战了那种认为只要学会某种‘技艺’(techne)就能获得真正智慧的观点。这种挑战,对于一个身处高度专业化分工的现代人来说,是极具颠覆性的。它迫使你去思考,一个优秀的政治家、教育家,他真正需要掌握的核心素养到底是什么?这种对‘本质’的不断挖掘和剥离,使得整本书充满了永恒的张力。它不是在解决一个具体的问题,而是在定义我们应该以何种姿态去面对所有问题。

评分这本厚厚的书,我拿到手的时候,光是封面那烫金的字体就透着一股子沉甸甸的历史感。说实话,我最初翻开它,是抱着一种朝圣般的心情。我期待着能从中窥见古代思想的脉络,那种未经后世繁复解读的,带着原始生命力的哲学思辨。然而,阅读的过程更像是一场迷宫探险。文字的密度需要极大的专注力去梳理,那些对话的来回推敲,仿佛能听到柏拉图笔下苏格拉底那标志性的、带着一丝嘲讽却又无比真诚的追问声。它不是那种能让你一口气读完的畅快之作,更像是一壶需要慢慢熬煮的浓茶,每一口都需要细细品味其中蕴含的涩与甘。我花了很长时间在那些关于“美德能否被教导”的辩论上打转,那种清晰的逻辑推演,即便是隔着两千多年的时光,依然能让人感到一种智力上的被挑战和激发。它不提供简单的答案,而是强迫你直面自己内心最根深蒂固的信念,然后,一步步地,用苏格拉底的‘助产术’,帮你把自己的想法剖开来看,这体验,着实是令人难忘的。

评分我不得不承认,第一次接触这套书的文字时,我的感觉是有些“晦涩”的。这绝非贬低,而是陈述一个普通读者在面对古典文本时的真实感受。它里面的某些论证链条跳跃性很强,如果不是事先对古希腊的政治和社会背景有所了解,很容易在某个环节掉队。我记得有那么一节,讨论的核心概念似乎一下子从城邦的治理转向了某个具体人物的美德定义,这种结构上的松散感,对于习惯了现代学术论文那种严丝合缝的论证体系的我来说,确实需要一个适应期。我不得不经常停下来,查阅一些背景注释,甚至需要对照着其他学者的导读才能勉强跟上苏格拉底抛出的那些看似不经意的反驳。但是,一旦你适应了这种对话的节奏,那种‘顿悟’的快感是无与伦比的。它让你意识到,很多我们今天习以为常的伦理判断,在那个时代就已经被如此彻底地审视过了。这本书,与其说是阅读,不如说是在参与一场历史悠久的思想法庭。

评分这四篇很好地呈现了柏拉图哲学中一个核心问题,即美德和知识的关系。

评分英文翻译不严谨,比如optative统统没翻出来。

评分整个暑假,语言快乐,深觉人文学科对人的侮辱之重

评分c.P1

评分整个暑假,语言快乐,深觉人文学科对人的侮辱之重

相关图书

本站所有内容均为互联网搜索引擎提供的公开搜索信息,本站不存储任何数据与内容,任何内容与数据均与本站无关,如有需要请联系相关搜索引擎包括但不限于百度,google,bing,sogou 等

© 2026 book.quotespace.org All Rights Reserved. 小美书屋 版权所有