具体描述

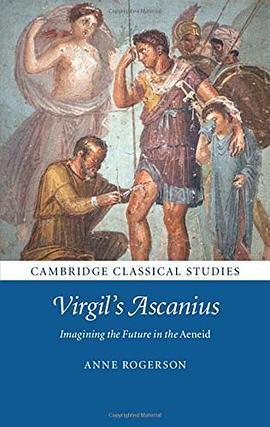

This fine and stimulating book discusses multivalent and slippery prophecies, significant names and their etymologies, and especially the importance of variant and inconsistent versions of myth. To quote Julie Andrews in The Sound of Music, “these are a few of my favorite things.” But even someone whose interests do not overlap with this book’s as thoroughly as mine will find much of value here.

The book, originally a dissertation supervised by Philip Hardie and Emily Gowers, has ten concise chapters including the introduction and conclusion. Different chapters explore conflicting statements about whether the Trojan Ascanius or Aeneas and Creusa’s half-Italian son Silvius Postumus will be heir to Aeneas and ancestor of the Alban Kings, Romulus, and the Julians; the significance of the names Ilus, Iulus, and Ascanius; the ways that “Ascanius is appropriated as a symbol” (p. 57) by female characters, both Dido and especially the backwards-looking and Troy-fixated Andromache in Aeneid 3; how the strong and problematic associations of Ascanius with Troy are stressed by Andromache, by Ascanius’ performing of the “Trojan Games,” and in other passages; how the omen of Ascanius’ flaming head in Aeneid 2 could be read in different ways, and how the similar omen in Book 7 furthers the idea that Lavinia’s line and that of Ascanius are to be in competition; how Ascanius is portrayed at times as an exotic and even “erotic, un-epic presence” (p. 138) who needs special protection, and at other times as an immature, rash boy lacking in self-control; and how these various worrisome qualities, and his persistent Trojanness, suggest that he might make a less suitable heir and ancestor than Silvius. Rogerson’s close reading of the details of the text, which builds both on context and on the poet’s precise word-choice, calls attention to many aspects of the poem that we have missed. The book offers a thoroughly modern way of reading: Rogerson is well-versed in the mythological background and makes solid philological arguments, but shares the modern scholar’s openness to ambiguity and uncertainty––when the details of the text support such a reading. Not every reader will agree with everything she says, but the arguments are careful and compelling.

Describing how the Aeneid often evokes potential future conflict between Ascanius and his family on the one hand and Lavinia and her son Silvius Postumus on the other is central to the book’s novel contribution, so I’ll give that question the most attention here. After a thoughtful Introduction, Rogerson begins in Chapter 2 with a review of Aeneas’ offspring in earlier versions of the story, many of which depict multiple sons or even daughters, and often feature conflict between Ascanius’ and Lavinia’s lines. These versions, including Livy’s recent declaration of aporia in Ab Urbe Condita 1.3.2-3, formed the context in which readers would have received Vergil’s new story. Of course a new poet is free to innovate, and to declare, e.g., that Aeolus is in need of a wife in Aeneid 1, rather than the married father of twelve of Odyssey 10. But Rogerson shows again and again that the poet’s careful word-choice points to rather than evades the problem of Aeneas’ heirs. She shows first that in numerous passages divine or divinely inspired figures state or imply that Ascanius will found Alba Longa and that his heirs will reign both at Alba and at Rome. These passages include Jupiter’s words to Venus in 1.267-74 and to Mercury in 4.234 (repeated by Mercury in 274-76, and cited by Aeneas in 355), Anchises' in 6 (the Parade of Heroes features Caesar et omnis Iuli / progenies magnum caeli uentura sub axem, 789-90), the description of Aeneas’ shield (genus omne futurae / stirpis ab Ascanio, 8.628-29), and Apollo’s addressing Ascanius as dis genite et geniture deos (9.642). But the problem is that Anchises also says that Aeneas’ half-Italian son Silvius Postumus will be “king and father of kings”: Siluius, Albanum nomen, tua postuma proles, / quem tibi longaeuo serum Lauinia coniunx / educet siluis regem regumque parentem, 763-65. The phrasing regem regumque parentem even resembles and points to Book 9’s dis genite et geniture deos. Silvius’ Alban nomen “becomes the cognomen of all the Alban kings hereafter ([Livy] 1.3.7), down to Numitor, father of Rhea Silvia, the mother of Romulus and Remus” (p. 19). Rogerson nicely notes that when Anchises introduces the Parade by speaking of “what glory is to come for Aeneas’ Dardanian offspring” (Dardaniam prolem … 6.756), Dardanius is not a bland adjective meaning “Trojan,” but evokes “Dardanus’ dual nature as both Trojan and Italian” (p. 28) and the “hybrid” nature he shares with Silvius Postumus, who is pointedly described as Italo commixtus sanguine (762).

When in Book 7 the flaming-head omen that marked Ascanius as special in Book 2 recurs in connection with Lavinia, “The repetition … casts Lavinia as the Ascanius figure for the second, Italian half of the poem” (p. 30). The oracle of Faunus tells Latinus that “foreign sons-in-law are coming to lift by blood our name to the stars” (7.98-99), and that “descendants from their stock” (quorumque a stirpe nepotes, 99) will see the whole world at their feet. “Their stock” means the stock of the foreigners, and so Faunus’ oracle will be true even if Ascanius is the ancestor and not Lavinia. (Rogerson might have compared 8.340-41, where Carmenta accurately prophesies greatness for the sons of Aeneas, but only for the site of Pallanteum––and not Evander’s people, who will die out, futuros / Aeneadas magnos et nobile Pallanteum). But Rogerson notes that no solution can make the problem go away, for neither Ascanius nor Silvius can be easily dismissed,1 nor can the problem be tamed as “a neutral, if playful allusion, in the style of an Alexandrian poet, to the variations in the tradition,” because “Aeneas’ descendants matter more than that” (p. 32). And the issue has contemporary relevance, which Rogerson touches on more than explores in depth: “Placed side-by-side the passages hint at civil strife to come after Aeneas’ settlement in Latium, a further allusion among many in the text to the perpetual struggles for power, inheritance and succession that tore at the fabric of Roman society, from the time before the actual foundation of the city to the age of Augustus” (p. 33). She could have stressed the Augustan context even more: in the last years of Vergil’s life, Augustus lost his nephew and son-in-law Marcellus in 23; he then gave Marcellus’ widow Julia, Augustus’ daughter by his previous marriage, in marriage to Agrippa (their first son Gaius was born in 20); and at the same time Augustus’ wife Livia had her two sons from a previous marriage, Tiberius (22 years old in 20) and Drusus (18 in 20). And of course Augustus was merely a great-nephew and adopted son of Julius Caesar, and had Caesar’s only son, Cleopatra’s Caesarion, killed. Ovidian scholars often note Ovid’s interest in questions of succession later in the Augustan period:2 Rogerson’s book suggests that Vergilians should join them. She notes in particular that in the wording of Anchises’ lament for Marcellus in Aeneid 6 we see “clear evocation of the rival claims of Silvius and Ascanius” (p. 34), in such details as Iliaca … de gente 875, Latinos / avos 875-76, Romula … tellus 876-77, and even heu, miserande puer, si qua fata aspera rumpas 882, which resonates with the language used of Silvius’ descendant Silvius Aeneas in 770, si umquam regnandam acceperit Albam.

Subsequent chapters treat well-known passages with a fresh eye, and continue to reveal how the poem promotes uncertainty about Ascanius’ future, stresses problematic aspects of his Trojanness, and raises doubt about his suitability to reign. Rogerson’s discussion of names in Chapter 3 notes that “Ascanius is an emblem of an illustrious past and the symbol of the dazzling future,” but that “he also embodies one of the Aeneid’s major concerns: how the Trojans are to leave enough of their Trojanness behind to become Roman.” Chapter 4, on “Andromache and Dido,” describes how “narrative paths not taken feature strongly in the early books of the Aeneid, where a number of dead ends threaten Ascanius and the Roman future he represents.” Andromache, who of course at Troy lost a son of Ascanius’ age, “is trying to claim Ascanius … as part of her own story” (p. 62), which involves living in a wan replica of Troy, and thinking of “Ascanius’ heroic inheritance” (p. 59) as something to gaze back upon, rather than looking forward to a new future. Rogerson says that “Andromache’s is one of the most outspoken voices of dissent from Jupiter’s program [in Book 1] of recovering from Troy’s fall by moving on to something different” (p. 59), but it should be noted that in speaking to Venus in Book 1 Jupiter stresses the Trojanness of the Romans much more than he does to Juno in Book 12. Chapter 5 discusses the lusus Troiae, the equestrian exercises at the funeral games for Anchises that the poet says Ascanius brought to Alba Longa (5.596-600), and that contemporary Romans preserved as an “ancestral rite” (600-602). Rogerson says that “Virgil’s contribution to the debate about Troy’s revival in the age of Augustus has gone virtually unremarked” (p. 86). She nicely discusses the ways in which the survival of the Trojan name in the lusus Troiae of Augustan Rome contradicts what Jupiter promises Juno in Book 12; as always, close reading of both text and context is the key, including in Rogerson’s treatment of the challenging phrase Troiaque nunc pueri (5.602). In later chapters Rogerson’s discussion of Ascanius’ killing of Numanus Remulus is particularly rich: in contrast to most scholars, she shows that “rather than a true initiation…., this episode is a ‘flirtation with adulthood’” (p. 163, borrowing a phrase of Llewelyn Morgan’s).

I like it when books are short but dense, and show evidence of much careful work and thought. This one is well-written, clear and generous. I would have cited my friend Mark Petrini’s chapter on Ascanius in his book on Catullus and Vergil even more times than Rogerson does, but she makes good use both of Petrini and of a wealth of Vergilian scholarship. On “substitution” in Aeneid 1 and 4, of Cupid for Ascanius and then Ascanius for Aeneas (in Dido’s eyes), I would add an interesting paper by Bowie.3 Another supplement: in discussing the flaming heads of Ascanius and Lavinia, Rogerson reminds us (p. 103) that “Cassius Dio tells the story of Salvidienus Rufus, a man of humble origins … whose rise was signalled by a flame that issued from his head as he was tending his flocks.” Better to add the end of the story, in which Salvidienus offers to betray Octavian to Antony, who tells Octavian, leading to Salvidienus’ execution or suicide. So that’s a flaming head associated with civil strife and failure, which makes it more relevant to Rogerson’s concerns.

Rogerson’s last sentence (p. 203) can also be mine: “Ascanius in the Aeneid is a troubling figure, but he is suited to the troubled times in which Virgil wrote, when the succession to Augustus was undetermined, Rome’s ability to move on from years of civil war unclear, and, as Evander says in relation to Pallas, Ascanius’ doomed double, ‘hope of the future uncertain.’”

作者简介

目录信息

读后感

评分

评分

评分

评分

用户评价

我一直认为,伟大的史诗往往隐藏着无数可以独立成篇的精彩故事。维吉尔的《埃涅阿斯纪》无疑是其中的佼佼者,而阿斯卡纽斯,这个名字本身就充满了历史的厚重感和命运的召唤。他不仅是埃涅阿斯的儿子,更是特洛伊的希望,是罗马诞生的重要参与者。然而,在宏大的史诗叙事中,他的个人经历和内心世界,似乎总是被掩盖在父亲的辉煌之下。这本书的出现,让我看到了一个深入探索这位年轻继承者内心世界的绝佳机会。我期待作者能够以精湛的笔触,将阿斯卡纽斯从一个符号性的存在,转变为一个有血有肉、有情感、有思想的个体。我希望看到他对父辈的敬仰,对家国的责任,以及在他成长过程中,那些可能存在的迷茫、恐惧与渴望。这本书能否让我们看到,在一个充满神谕和战争的时代,一个年轻的王子,是如何在历史的洪流中找到自己的位置,如何承担起属于他的使命,并最终成为那个改变命运的关键人物,是我最期待的地方。

评分作为一名对古典神话和历史有着浓厚兴趣的读者,我常常沉醉于那些古老的故事和人物。维吉尔的《埃涅阿斯纪》是我心中的一座丰碑,而其中关于阿斯卡纽斯的部分,虽然篇幅不多,却总能引起我无尽的遐想。他承载着特洛伊的血脉,也预示着罗马的未来,他的存在本身就充满了象征意义。我一直觉得,在一个宏大的神话叙事中,那些处于核心人物身边的人物,往往隐藏着更为细腻和复杂的情感。所以,当看到《Virgil's Ascanius》这本书时,我的好奇心瞬间被点燃了。我猜想,这本书一定是对阿斯卡纽斯这一形象的一次深入挖掘和重塑。它是否会探讨他在家族使命、个人情感以及时代洪流中的挣扎?是否会描绘他在成长过程中所面对的挑战,以及这些挑战如何塑造了他的性格?我非常期待这本书能够从一个全新的角度,为我们展现阿斯卡纽斯的内心世界,让我们能够更深刻地理解他,感受他,仿佛他就是我们身边的一个鲜活的人物,他的故事,也能够引起我们今天的共鸣。

评分这本书的装帧设计让我一眼就爱上了,沉甸甸的质感,封面上那古朴而富有力量的插画,瞬间就将人带入了一个遥远的时代。我迫不及待地翻开了第一页,纸张散发着淡淡的墨香,那种触感,仿佛能感受到古籍的温度。我本身对古典文学就颇有研究,特别是古罗马时期,所以当我知道有这样一本关于阿斯卡纽斯的作品时,内心充满了期待。我知道,阿斯卡纽斯,维吉尔笔下那位被命运选中的继承者,他的故事往往隐藏在宏大的史诗之下,是连接神话与现实的关键一环。这本书的出现,让我看到了深入挖掘这位传奇人物内心世界的可能性。我猜想,作者一定花费了大量的时间去考据,去理解那个时代的社会风貌、宗教信仰,以及最重要的,那些塑造了阿斯卡纽斯性格和命运的复杂情感。是单纯的使命感驱使着他,还是内心深处也藏着属于自己的渴望?这本书能否将这些隐藏的情绪具象化,让读者仿佛能与他一同经历那些风雨,一同感受那份沉甸甸的责任,是我最为好奇的部分。我期待这本书能带来一场思想的盛宴,用细腻的笔触揭示历史长河中那些闪耀而又常被忽视的个体光芒。

评分我通常对历史小说类的作品保持着一种挑剔的态度,因为太多作品只是披着历史的外衣,骨子里却充斥着现代的价值观和想象。然而,当我在书店看到《Virgil's Ascanius》时,它的名字本身就吸引了我。维吉尔,那个名字本身就代表着史诗的厚重与艺术的高度。而阿斯卡纽斯,作为埃涅阿斯的儿子,特洛伊的继承者,他的命运与罗马的诞生紧密相连。我一直在思考,在那些波澜壮阔的战争和神谕的背后,一个年轻的王子,一个被寄予厚望的继承人,他的内心世界究竟是怎样的?是无畏的勇士,还是充满迷茫的少年?这本书能否在宏大的叙事中,捕捉到那份属于个体的挣扎与成长?我非常期待作者能否用一种更加人性化、更加贴近读者情感的方式来呈现阿斯卡纽斯。我希望看到的不只是他完成神谕的使命,更能看到他在过程中所经历的内心转变,那些关于责任、关于牺牲、关于爱与失去的思考。我渴望这本书能提供一种全新的视角,让我们能够超越古老的文本,去感受一个活生生的人物,他的喜怒哀乐,他的勇气与脆弱。

评分从这本书的题目我就感受到了它潜在的深度。阿斯卡纽斯,这个名字在《埃涅阿斯纪》中虽然不至于是主角,但其重要性不言而喻。他是特洛伊的希望,是罗马未来的奠基者之一。然而,比起他父亲埃涅阿斯那种被命运推着走的悲壮,阿斯卡纽斯似乎更像是一个被赋予了使命的象征。我一直在想,在维吉尔那充满史诗韵味的笔触下,阿斯卡纽斯是如何被塑造的?他的内心是否也曾有过动摇?在漫长的迁徙和征战中,他是否也曾对未来感到迷茫?这本书的出现,就像是为我们打开了一扇通往阿斯卡纽斯内心深处的窗户。我迫切地想知道,作者将如何描绘他的童年,他的成长,以及那些塑造了他性格的关键时刻。是否会有他与父亲之间不为人知的对话?是否会有他独自面对艰难抉择的场景?我期待这本书能够填补那些历史文本中的空白,用生动的想象和深刻的洞察,为我们呈现一个更加立体、更加鲜活的阿斯卡纽斯,让他不再仅仅是一个符号,而是一个有血有肉、有情有义的灵魂。

评分 评分 评分 评分 评分相关图书

本站所有内容均为互联网搜索引擎提供的公开搜索信息,本站不存储任何数据与内容,任何内容与数据均与本站无关,如有需要请联系相关搜索引擎包括但不限于百度,google,bing,sogou 等

© 2026 book.quotespace.org All Rights Reserved. 小美书屋 版权所有