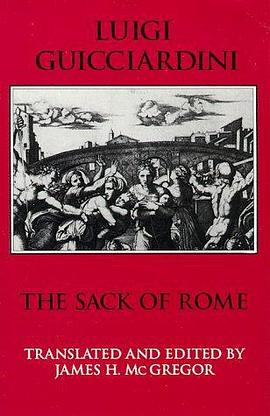

The Sack of Rome pdf epub mobi txt 电子书 下载 2026

- History

- 糖果

- Renaissance

- Italy

- European-History

- 历史

- 罗马帝国

- 古代史

- 军事史

- 劫掠

- 衰落

- 西哥特人

- 瓦伦丁三世

- 西罗马帝国

- 410年

具体描述

The Sack of Rome of 1527 is one of the best known events of Renaissance Italy. Every Italian chronicle written at that time gives room to what must have seemed like a new barbarian invasion, probably because many of those who sacked the city were Lutheran. The Florentine Luigi Guicciardini, who was forty-nine of age when Rome was taken by storm, held the office of Gonfaloniere di Giustizia in 1527 and had his brother, the famous writer and historian Francesco, as lieutenant of the papal forces. Thus, he was in a good position to judge the events leading to the sack.

Guicciardini's work, which is dedicated to the duke of Florence Cosimo I, wants not only to reconstruct what happened but also the reasons for it. He believes that the starting point of all Italian ruins is the invasion of King Charles VIII of France in 1494. Before this date the Italian states were strong and secure, but from then on there have been a number of wars, plunders and plagues. By reading this, it is clear that Guicciardini's view of the past is rather idealized, for even before Charles VIII Italy was not without accidents. Yet the author, a man of long political experience, knows very well which problems statesmen have to face and how bad governments can provoke ruin and disasters. In fact, in his opinion the sack of Rome is almost a natural outcome of the countless errors of the League of Cognac. This treaty, signed by England, France, Florence, Venice, Milan and the Papacy against Emperor Charles V in 1526, begins "without money and leadership," writes Guicciardini. Its military commander within Italy, Francesco Maria della Rovere, lacks of energy and courage, being adverse to dangers and difficulties and unable to seize good opportunities. He insists that the most prudent way to win the enemy is with the sword in its scabbard. Guicciardini shows no sympathy for him and from time to time attacks him for his inability to be an outstanding general. Although Francesco Maria puts the blame on his soldiers, they do not deserve it. In Guicciardini's mind if Italian soldiers are overwhelmed and beaten, it is not because of poor military skill, but because they do not have good commanders to mould them and bring out their natural aggressiveness. While Francesco Maria is unsuitable for his position, Giovanni de' Medici, Duke Cosimo I's father, towers above his comrades. He is the only one among the Italian leaders who can fight the German Landsknechts effectively, and he would defeat the enemies by harassing them. Unfortunately, he is mortally wounded near Borgoforte, and Guicciardini finds his death the turning point of the war, for without him the German can go on southwards.

Before describing the sack of Rome, Guicciardini devotes much room to the events leading to such a disaster. Being a politician, he recognizes that money plays a cardinal role in wars. Soldiers cannot fight without being paid, for if so they are prone to mutiny, as happens to the Spanish of the Imperial army, who almost kill their commander, Duke Charles of Bourbon. So, if an army can be a bulwark against the enemy, it can turn out to be a menace to its employers. In order to avoid such dangers a citizen militia becomes the key if a state wants to be secure, a thought similar to that of Machiavelli.

After a long and detailed narration of the war in northern Italy and perhaps too long a description of an uprising within Florence against the government, Guicciardini focuses his attention on the fall of Rome. Here his narration comes to its climax and provides many memorable episodes, for instance a cardinal who takes shelter in Castel Sant'Angelo by having himself hauled up in a basket on cables dropped from above, or like others, taken prisoner by the Imperial soldiers, who prefer to commit suicide rather than endure other tortures. It would be easy, Guicciardini says, to defend Rome by cutting its bridges, but once again Pope Clement VII and his men show their inability to face adversities. The story ends with the powerful image of the pope looking towards the sky with tears in his eyes and mourning: "Wherefore, then, hast thou brought me forth out of the womb? Oh, that I had died, and no eye had seen me." [Job. 10:18]

James H. McGregor, now a professor of comparative literature at the University of Georgia, made a praiseworthy contribution to knowledge of Renaissance Italy, making a little-known text available to English-speaking readers. It is a shame, but not McGregor's fault, that the original book was converted into 19th-century Italian, as was the common fate of other works such as Marin Sanudo's Commentarii della guerra di Ferrara tra li Viniziani ed il duca Ercole di Este nel MCCCCLXXXII (Venice, 1829). In order to allow the reader to understand Guicciardini's work more clearly, McGregor provides an useful and instructive introduction, in which he explains who the author was, his role as a historian and the events leading up to the sack. At the end there is an afterword, a concise bibliography and a glossary, which are extremely useful in managing some obscure names and ranks. A few nice illustrations, taken from old engravings and woodcuts, show some of the monuments quoted in the text such as the Castel Sant'Angelo and the Castello Sforzesco in Milan. Perhaps it would have been interesting to see a map of the route of the Imperial army, but we do have one of the most important places of the war theatre. There are a few mistakes of secondary importance, for instance Castiglione d. [delle] Strivieri (instead of Castiglione delle Stiviere), or San Giovanni in Persicelo (instead of San Giovanni in Persiceto), and Duke Alfonso d'Este of Ferrara was not born in 1486 but in 1476. Despite these, McGregor's admirable work has been of great use both to scholars and students alike. Guicciardini's almost obscure work deserves much more attention both from Italian and foreign readers as a valuable source concerning Renaissance Italy.

作者简介

Luigi Guicciardini (1478-1551) was the eldest son of Piero Guicciardini (1454-1513). The Guicciardini had been an important family in Florence since the 14th century, and both Piero and Luigi are names that recur throughout the genealogy. The family, which still survives and still lives in the Palazzo Guicciardini, became wealthy and prominent as owners of silk factories, Their wealth quickly led them to positions of political power.

Luigi Guicciardini himself seems to have had little interest in or inclination for business. His political career on the other hand was very active. He held political office firt in 1514, when at the age of 36 he was appointed consul for the sea in the Florentine-controlled government of Pisa. In 1517 he was made commissioner of Arezzo. The following year he was elected one of the priors of Florence for the months of January and February. He served as commissioner again in 1521 and 1526, first in the small city of Castrocaro and afterwards in Pisa. In March and April of 1527, at the very height of the events he narrates in his History, he was appointed to the supreme executive office in Florence, that of gonfaloniere di giustizia. While he held that office, a political coup was attempted that would have removed the Medici from power. Luigi's role in the coup has been regarded by some as pivotal, and he has been blamed for failing to support either the rebels or the Medici.

Although he sympathized with those opposing Medici government, Luigi's political views were by no means democratic. Though he distrusted the Medici, Luigi Guicciardini, in company with all those Florentines who shared his views, found himself with no viable political alternative to them and increasingly served their interests. He was one of the consultants to Pope Clement VII on the reorganization of the Florentine government after 1530. He served on the Medici-controlled Senate in 1532, and throughout the remainder of his life held numerous state offices under them.

目录信息

Preface

Introduction

The Sack of Rome (Dedication, Book I, Book II)

Afterword

Bibliography

Glossary

Maps (Bourbon's March on Rome, The Sack of Rome)

· · · · · · (收起)

读后感

评分

评分

评分

评分

用户评价

这本书的叙事结构堪称精妙,它采用了多线并进的手法,将不同地域、不同阶层的故事巧妙地编织在一起,形成了一幅宏大而又细节丰富的时代图景。我仿佛能闻到那不同城市中弥漫的烟火气、腐败味和新生的泥土芬芳。最让我感到震撼的是作者对“理性”与“迷信”之间拉锯战的捕捉。在社会结构崩塌的边缘,人们对逻辑和科学的信任开始瓦解,转而寻求更直接、更原始的精神寄托,这种心理转变的描写,细腻入微,极具说服力。尤其是书中几处关于知识传承中断的描写,那种墨香的消逝与卷轴的腐朽,象征着一个时代的智识财富正在化为尘土,那种痛惜感是难以言喻的。它不是一本简单的历史记录,更像是一部心理史学作品,探讨的是在巨变面前,人类共同体的集体无意识是如何被重塑的。我尤其喜欢作者在描述那些关键转折点时,所展现出的那种克制而有力的叙事节奏,绝不拖泥带水,却又信息量巨大。

评分啊,这本新近读完的史诗巨著,着实让人沉醉其中,思绪万千。它并非聚焦于某一个帝国的倾覆,而是以一种近乎散文诗的笔触,描绘了文明在历史洪流中无可避免的衰变与重塑。作者对于那种“黄金时代”消逝后,残存的文化精英如何试图在废墟之上重建秩序的描绘,尤其深刻。我特别欣赏他对那些小人物的刻画,那些在宏大叙事下被忽略的工匠、哲人、甚至仅仅是幸存者,他们如何以最微弱的火花,抵抗着黑暗的侵蚀。书中对建筑美学衰退的描写,从宏伟的拱顶到朴素的砖石,无声地诉说着精神世界的失落,那种从追求永恒到屈服于瞬间的转变,令人唏嘘。它没有提供廉价的答案或英雄主义的慰藉,反而迫使读者直面历史的残酷与循环,让人在合上书卷后,久久无法摆脱那种历史的厚重感压在心头。文字的驾驭极其老练,时而如疾风骤雨,描摹战乱的混乱;时而又如古井之水,沉静地反思权力与信仰的本质,读来酣畅淋漓,回味无穷。

评分这本书最让我印象深刻的,是它处理“时间”的方式。作者仿佛拥有驾驭时间洪流的能力,能够在几页之内跨越数百年,又能在寥寥数句中捕捉到某个关键人物生命中至关重要的一秒钟。这种对时间感知的自由切换,使得历史不再是线性的瀑布,而是螺旋上升或下降的迷宫。它对“记忆”的探讨也极为精妙,当官方记录开始模糊、当口头传说开始扭曲时,历史是如何被新的叙事所取代和“净化”的?书中对于不同派系如何争夺对过去的解释权力的描写,非常具有当代意义。这不仅仅是关于过去的倾覆,更是关于“如何铭记”的永恒困境。全书的基调是冷峻的,但笔触却充满了一种知识分子的悲悯情怀,它既是历史的记录者,也是对人类集体健忘症的深刻批判者。读完之后,感觉像是经历了一场漫长而必要的精神洗礼,对理解当前世界的复杂性,有了全新的参照系。

评分坦白说,这本书的阅读门槛略高,它要求读者对当时的社会背景、宗教哲学有一定的了解,但一旦进入状态,那种知识被激活的快感是无与伦比的。作者的遣词造句极其考究,许多段落简直可以单独摘出来作为文学典范。比如他描述那场决定性的战役,不是聚焦于刀光剑影,而是侧重于军令传达的失真、士气崩溃的瞬间以及指挥官眼中映出的绝望星光。这种由微观折射宏观的手法,极具张力。更值得称道的是,它成功地避开了将历史简单化为“好人”与“坏人”的二元对立。书中的人物形象丰满得可怕,即便是最卑劣的篡位者,也保有其复杂的人性光辉,而最虔诚的殉道者,也难免沾染权力的泥淖。这种对人性的深刻洞察,让整部作品摆脱了教条主义的窠臼,成为了对人类境遇的深刻探讨。

评分我必须承认,这本书的阅读体验是有些“沉重”的,但这种沉重感是经过精心设计的,它并非无谓的悲观,而是一种必要的反思。作者通过对一系列缓慢而又不可逆转的衰败过程的细致梳理,构建了一种强大的历史宿命感。它不像许多流行历史读物那样试图提供一个清晰的英雄路线图,相反,它更关注那些“失败”的、被遗忘的尝试。比如,书中花费了大量篇幅去追溯某个地方性文化如何在外来冲击下艰难维持其特性,那种挣扎和最终的妥协,读起来令人心酸。文字的密度极高,我常常需要停下来,细细咀嚼那些描述社会结构瓦解的句子,它们像精密的钟表齿轮一样咬合在一起,展示出系统性崩溃的必然逻辑。如果你期待的是那种一气呵成的爽快叙事,这本书可能不太适合你,但如果你渴望深层次的、多维度对文明形态进行解剖,那么它绝对是一座富矿。

评分i created this item on douban. excellent book.

评分i created this item on douban. excellent book.

评分i created this item on douban. excellent book.

评分i created this item on douban. excellent book.

评分i created this item on douban. excellent book.

相关图书

本站所有内容均为互联网搜索引擎提供的公开搜索信息,本站不存储任何数据与内容,任何内容与数据均与本站无关,如有需要请联系相关搜索引擎包括但不限于百度,google,bing,sogou 等

© 2026 book.quotespace.org All Rights Reserved. 小美书屋 版权所有